by Martin J. Greenberg and Dan MacMillan

I. Introduction: What are Cost Overruns

As stadium construction costs continue to rise, there is an increasing amount of scrutiny devoted to the contractual obligations of the interested parties that make up the public-private partnership. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, cost overruns have become “almost a natural part of building and infrastructure projects.”[1] It is imperative that public and private participants in the sports facility development process allocate financial responsibility through their contracts to address the real threat of construction cost overruns.

Cost overruns are broadly defined as the amount by which a construction contract’s actual costs exceed the budgeted, estimated, original, or targeted costs.[2] Cost overruns are a major source of concern for parties to construction contracts, as unforeseen circumstances and unavoidable variances are inherent in any construction project. The construction and development of sports and entertainment venues pose no exceptions in the realm of cost overruns.

There are many root causes that contribute to cost overruns. In 2016 an International Association of Engineering Insurers Working Group (“IMIA”) reported that errors in budgeting, expenses required beyond the scope of work, and tools and equipment costs exceeding the project allocation were generally the most common reasons for cost overruns.[3] The IMIA concluded that more specific factors include, but are not limited to:

There are many root causes that contribute to cost overruns. In 2016 an International Association of Engineering Insurers Working Group (“IMIA”) reported that errors in budgeting, expenses required beyond the scope of work, and tools and equipment costs exceeding the project allocation were generally the most common reasons for cost overruns.[3] The IMIA concluded that more specific factors include, but are not limited to:

- Ineffective project governance, management and oversight;

- Unanticipated site conditions;

- Poor project definition;

- Poor risk identification, management and response strategy;

- Imposed cash constraints and delayed payment;

- Skilled labor availability;

- Inexperienced management team;

- Design errors and omissions leading to scope growth and/or re-work;

- Poor project controls (cost & schedule);

- Inaccurate estimating.[4]

Moiz Noorani (“Noorani”), an expert writer for Project-Management.com concludes that it is rare that a project is completed within its estimated budget, and while planning is key to a successful construction venture, problems will persist regardless of the quality of the original plan.[5] Noorani details several factors that he believes contribute to cost overruns:

- Underfinancing;

- Unfeasible Cost Estimates;

- Underestimating the Project Complexity;

- Prolonged Project Schedule;

- Lack of Backup Plan;

- Lack of Resource Planning.[6]

In a thesis entitled Mitigation Measures for Controlling Time and Cost Overrun Factors, the author concludes that the following factors contribute to cost overruns:

- Incompetent subcontractors

- Schedule delay

- Inaccurate time and cost estimates

- Mistakes during construction

- Frequent design changes

- Mistakes and errors in design

- Cash flow and financial difficulties faced by contractors

- Financial difficulties of owner

- Delay in progress payment by owner

- Delay payment to supplier/subcontractor

- High cost of labor

- Labor absenteeism

- Fluctuation of prices of materials

- Shortages of materials

- Late delivery of materials and equipment

- Equipment availability and failure

- Change in scope of the project.[7]

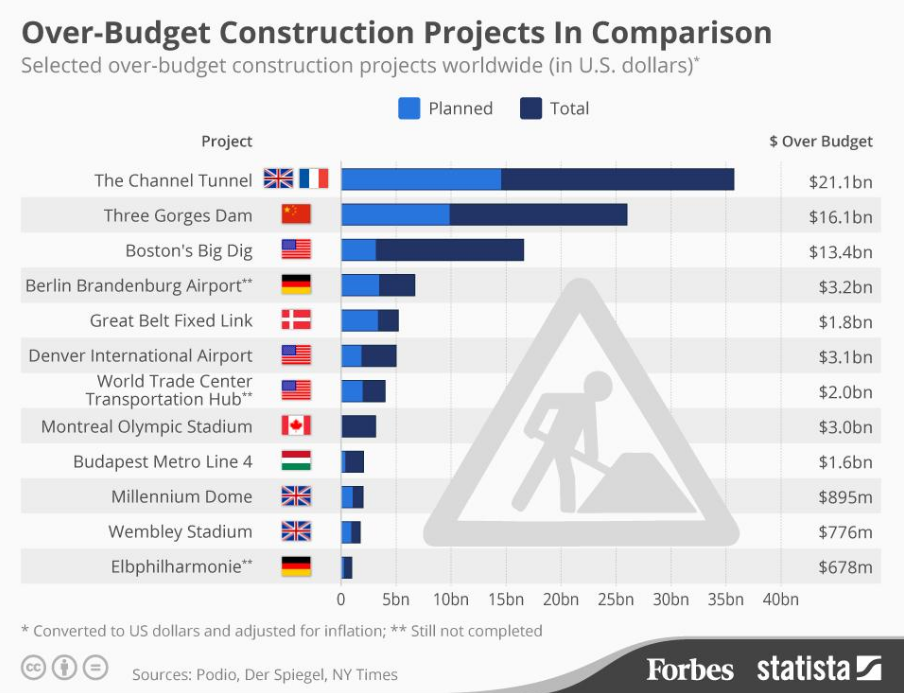

Well known projects worldwide have experienced construction overruns or over budget expenditures.[8]

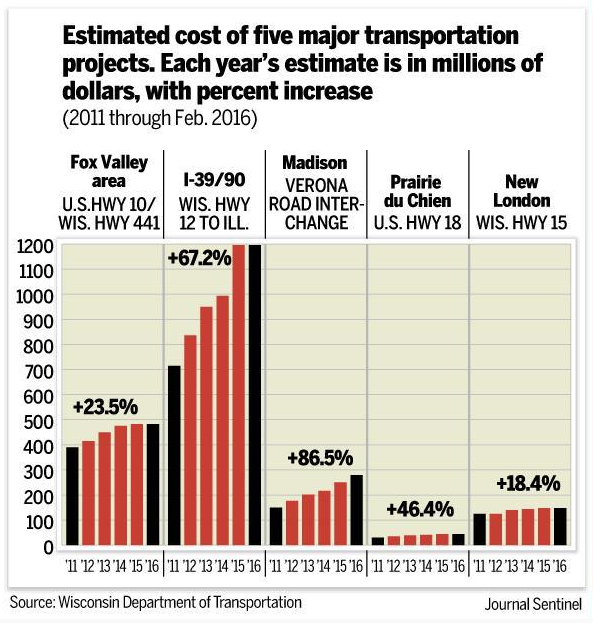

In southeastern Wisconsin, highway project delays have accumulated more than $700 million in construction cost overruns.[9]

Construction cost overruns have become common and contentious in the construction industry, and it is increasingly important to manage risks throughout the process in order to prevent unwanted consequences.[10] The construction and development of professional sports venues are greatly impacted by the problem of cost overruns. Politicians and communities can become very upset over project delays and the appropriation of funds when public tax dollars are in the balance. Though cost overruns are not unique to the sports industry, the repercussions are more evident given the visibility and popularity of modern American professional sports, and the fact that the public is footing part of the bill. Contracts determine who bears the obligation of cost overruns.

Construction cost overruns have become common and contentious in the construction industry, and it is increasingly important to manage risks throughout the process in order to prevent unwanted consequences.[10] The construction and development of professional sports venues are greatly impacted by the problem of cost overruns. Politicians and communities can become very upset over project delays and the appropriation of funds when public tax dollars are in the balance. Though cost overruns are not unique to the sports industry, the repercussions are more evident given the visibility and popularity of modern American professional sports, and the fact that the public is footing part of the bill. Contracts determine who bears the obligation of cost overruns.

An interview with Barry LePatner, a Construction Attorney with LePatner & Associates, examined the mass inflation that has plagued construction projects for the last twenty years.[11] LePatner details that an imbalance in information is at the core of many busted budgets.[12]

The detailed nature of construction product and service pricing is often difficult for team owners to understand, which is beginning to lead to a major paradigm shift in the construction industry.[13] Whereas it was typical for the lowest bid to win a particular contract, regular cost overruns and change orders have forced owners to abandon the assumption that the lowest bid will the most cost-effective.[14]

LePatner arges that there is no reason for stadium-sized projects “[n]ot to be built to the exact design specifications that were submitted, for a true complete price.”[15] The aforementioned information gap combined with pressure from construction managers to meet deadlines has created a pattern of ‘fast tracking’ projects without completed designs.[16] LePatner asserts that excessive change orders and additional design drawings are frequently associated with a ‘fast-tracked’ stadiums and will lead to 20-30% price increases.[17]

Today, construction loans are regularly secured with no less than 40-50% of the required equity, which has only tightened project margins.[18] Moreover, these price increases are borne by the end consumer as owners are unable to secure last minute commitments from public entities or mezzanine lenders.[19] Inflated prices have only led to owner attempts to recover massive budgetary gaps by selling seat licenses and increasing prices on food, drinks, apparel, and parking.[20]

Cost overruns are often borne by the construction company, construction manager, the team, or another obligated party as specified in a lease, development, or finance agreement. One expert in the construction industry estimates that “cost overruns of 15-25% have become acceptable as a normal part of the construction process.”[21] Moreover, “the fact that lenders recommend a 20% contingency in their lending terms is a testament to this recognized standard for construction projects.”[22] Given the high probability of construction cost overruns, situations where overruns are billed to the public are all-together too common. Contract delays can have an adverse effect on both the owner of the property and the contractor responsible for the construction, and this contentious relationship may lead to conflicts that can only be resolved by a court.[23] Therefore, cost overruns have a tremendous impact on construction projects including “increased cost, a delayed project completion date, loss of income/ROI to the owner and additional revenue for the contractor, time and cost delays for demolitions and/or re-work, and a possible increase in the contractor’s overhead.”[24]

Cost overruns are often borne by the construction company, construction manager, the team, or another obligated party as specified in a lease, development, or finance agreement. One expert in the construction industry estimates that “cost overruns of 15-25% have become acceptable as a normal part of the construction process.”[21] Moreover, “the fact that lenders recommend a 20% contingency in their lending terms is a testament to this recognized standard for construction projects.”[22] Given the high probability of construction cost overruns, situations where overruns are billed to the public are all-together too common. Contract delays can have an adverse effect on both the owner of the property and the contractor responsible for the construction, and this contentious relationship may lead to conflicts that can only be resolved by a court.[23] Therefore, cost overruns have a tremendous impact on construction projects including “increased cost, a delayed project completion date, loss of income/ROI to the owner and additional revenue for the contractor, time and cost delays for demolitions and/or re-work, and a possible increase in the contractor’s overhead.”[24]

II. Case Study of the Harmful Effects of Poorly Allocated Cost Overruns: Cincinnati Bengals

A. Introduction

Cost overruns can impact all parties involved in a construction project, but overruns can cause an enormous burden on a governmental unit that agreed to fund a stadium. As of 2010, taxpayers had shelled out about $10 billion more than originally budgeted to construct the more than 100 major-league stadiums in the United States.[25] Of these examples, the stadium financing disaster in Cincinnati, Ohio is useful to observe the detrimental effects of publically borne cost overruns.

As of 2016, Hamilton County had spent $920 million for the construction, development, and operation of Paul Brown Stadium, home of the Cincinnati Bengals (“Bengals”) of the National Football League (“NFL”).[26] When taxpayers voted to approve a tax increase to pay for new stadiums for the Cincinnati Bengals and Reds in 1996, [27] they were promised the continued existence of the professional franchises in Cincinnati, the lowering of property taxes and the creation of a revenue-producing Ohio River business district. [28] Today, those promises have remained unfulfilled—taxes have been raised, revenues from the facilities stagnated, and Hamilton County is obligated to pay $2.7 million or more in game-day operating costs.[29] By the expiration of the lease term in 2026, the estimated total public contribution will exceed $1.1 billion dollars.[30]

B. Bengals 1997 Lease Agreement – Hamilton County Responsible for Overruns

The 1997 Lease Agreement (the “Lease”) signed between The Board of Commissioners of Hamilton County, Ohio (the “County”) and Cincinnati Bengals, Inc. was predicated upon the original Memorandum of Understanding signed between the County and the City of Cincinnati, which levied a half-cent sales tax in order to fund the construction of Paul Brown Stadium for the Bengals and Great American Ballpark for the Reds.[31] Though the construction of Great American Ballpark was no simple task, the Reds promised to pay for all construction cost overruns in order to shield the taxpayers from financial liability.[32] Thus, th focus of the section will be the disastrous financial obligations imposed by the construction of the Paul Brown Stadium.

The redevelopment of the riverfront district was intended to “keep competitive and viable major league football and baseball teams” in Cincinnati.[33] A 1996 report by the Center for Economic Education at the University of Cincinnati determined that the new stadium ventures were estimated to bring in $296 million a year in new spending to the City.[34] However, it is clear that the Lease was crafted to prioritize the construction of the stadium at all costs rather than protecting the public investment.[35] Though officials were excited at the outset for the opportunities associated with construction of the new stadium and other riverfront developments, Hamilton County would quickly realize the error in their agreement to finance Paul Brown Stadium.

The Lease was clearly drafted to grant a large amount of influence to the Bengals over County expenditures, giving the Bengals the power of the purse—the County’s purse.[36] The Lease contains paragraphs granting broad latitude over construction decision making, and a small concluding provision that would exempt the County from performance of its obligation in the case of a material breach by the Bengals. Article 3 of the Lease established that the County owned a 100% undivided fee interest in the property, and Article 10 set out rights to revenues generated at the stadium facility.[37] While the County was responsible for all construction cost overruns and owned a ‘100% interest’ in the property, the Bengals still managed to reserve the rights to all revenue generated on Game Days, and even 11% of all revenues collected from the County-owned parking structure.[38]

The Lease was clearly drafted to grant a large amount of influence to the Bengals over County expenditures, giving the Bengals the power of the purse—the County’s purse.[36] The Lease contains paragraphs granting broad latitude over construction decision making, and a small concluding provision that would exempt the County from performance of its obligation in the case of a material breach by the Bengals. Article 3 of the Lease established that the County owned a 100% undivided fee interest in the property, and Article 10 set out rights to revenues generated at the stadium facility.[37] While the County was responsible for all construction cost overruns and owned a ‘100% interest’ in the property, the Bengals still managed to reserve the rights to all revenue generated on Game Days, and even 11% of all revenues collected from the County-owned parking structure.[38]

Exhibit C of the Lease Agreement set forth the budget for the ‘base stadium’ to include: (1) direct construction costs, (2) furniture, fixtures and equipment, (3) permits and assessments, (4) construction management fee, (5) construction contingency, (6) design contingency, (7) escalation, (8) allocable portion of design fees and other owner direct costs (including project management fees, for a an estimated cost of $269,913,934.[39] Because the Lease was signed before design plans were finalized, the Lease was entered into upon an understanding that plans would be bargained for in the future.[40] If the County were to disapprove of the Bengals’ plans it could either increase the budget to accommodate the plans, or submit revised plans to be approved by the Bengals.[41] The term of the Lease was to run from May 29, 1997 (“Commencement Date”) to June 30, 2026 (“Expiration Date”).

Not to be overlooked, Article 12 of the Lease creates a County obligation to provide ‘Level I Stadium Enhancements’ as determined by the existence of such enhancements in fourteen other NFL stadiums.[42] According to the Lease, ‘Level I Enhancements’ include “[n]ew stadium-related Improvement which is not available in stadia as of January 1, 1997 or, if then available in some form, is not currently prevalent in existing NFL stadia of such date, which is capable of being added within the structural confines of the Stadium Complex.”[43] The Lease provides several examples of what could be considered a ‘Level I Enhancement:’ (1) ticketless entry system, (2) stadium self-cleaning machines, (3) holographic replay system, (4) smart seats, (5) new forms of playing field surface, (6) next generation video screen, (7) next generation sound system, and (8) premium seating products different from private suites of club seats. Host of HBO’s Last Week Tonight, John Oliver, summarized the contingency deal in saying that “[t]he Bengals have a deal whereby if someone invents holographic instant replay in the future, the [C]ounty will pick up the tab.”[44] The Lease is chock-full of rights granted to the Bengals whereas the County incurred large financial obligations without the receipt of greater rights to determine necessary improvements or to collect full revenues from use of the facility.

Not to be overlooked, Article 12 of the Lease creates a County obligation to provide ‘Level I Stadium Enhancements’ as determined by the existence of such enhancements in fourteen other NFL stadiums.[42] According to the Lease, ‘Level I Enhancements’ include “[n]ew stadium-related Improvement which is not available in stadia as of January 1, 1997 or, if then available in some form, is not currently prevalent in existing NFL stadia of such date, which is capable of being added within the structural confines of the Stadium Complex.”[43] The Lease provides several examples of what could be considered a ‘Level I Enhancement:’ (1) ticketless entry system, (2) stadium self-cleaning machines, (3) holographic replay system, (4) smart seats, (5) new forms of playing field surface, (6) next generation video screen, (7) next generation sound system, and (8) premium seating products different from private suites of club seats. Host of HBO’s Last Week Tonight, John Oliver, summarized the contingency deal in saying that “[t]he Bengals have a deal whereby if someone invents holographic instant replay in the future, the [C]ounty will pick up the tab.”[44] The Lease is chock-full of rights granted to the Bengals whereas the County incurred large financial obligations without the receipt of greater rights to determine necessary improvements or to collect full revenues from use of the facility.

C. Construction of Stadium Facility and Audit

Bengals President Mike Brown broke ground on the Stadium Complex on April 26 of 1998 before 3,000 of the Bengals’ faithful, and a group of individuals donning their ‘Shoot Me – I Voted For the Stadium Tax’ shirts in protest.[45] Afterward, Brown expressed his pride in being a catalyst for bringing major redevelopment to Cincinnati’s riverfront district, despite the outcry over the large public expenditure.[46]

Bengals President Mike Brown broke ground on the Stadium Complex on April 26 of 1998 before 3,000 of the Bengals’ faithful, and a group of individuals donning their ‘Shoot Me – I Voted For the Stadium Tax’ shirts in protest.[45] Afterward, Brown expressed his pride in being a catalyst for bringing major redevelopment to Cincinnati’s riverfront district, despite the outcry over the large public expenditure.[46]

A year after the facility opened in 2000, the County hired New York auditors PricewaterhouseCoopers to review $51 million in cost overruns expensed during the construction of Paul Brown Stadium.[47] The process for the project guaranteed maximum price (“GMP”) and potential revisions is included in Article 4.6 of the Lease, and the original GMP amount of $269,913,934 is contained in Exhibit C of the Lease.[48] Auditors reviewed more than 400 changes to the stadium GMP and determined that more than 70% of the unrecoverable overruns were a result of incomplete designs and subsequent revisions.[49] Expenditures rose steadily as the designs were perfected and finalized, and the original GMP was quickly pushed aside.[50]

Cost overruns are undoubtedly related to poor planning and disagreements among project designers and funding partners, and such issues were not addressed in the creation of the Lease’s mutual covenants. Project Director W. Shelby Reaves asserted that the rush to open the stadium on time was at the core of the extensive cost overruns.[51] “The stadium simply would not have opened by [the start date] if construction managers waited for set pries for each change order before the work started . . . there was an insufficient contingency fund for the stadium from the beginning.”[52]

D. Hamilton County Looks to Offset Losses

The battle to recover taxpayer funds ensued when outraged County resident Carrie Davis brought suit alleging that the NFL had improperly pressured the City of Cincinnati and Hamilton County into greenlighting the Bengals’ new stadium.[53] In the suit, Plaintiff Davis alleged that “[t]he NFL violated federal anti-trust provisions by using its monopoly to extort new stadiums at highly favorable lease terms from communities. . . .[t]he bottom line is the NFL lied not just to . . . County residents but to numerous communities across the country to make taxpayers fund a private enterprise.”[54] The original lawsuit before the Hamilton County Common Pleas Court named the Bengals and all thirty-one other NFL franchises, accusing them of fraud, civil conspiracy, antitrust violations, and breach of contract.[55] Later in 2004, U.S. District Judge S. Arthur Spiegel determined that the County did have legal standing to bring the case, dismissing the arguments from the NFL.[56] The case was later brought before the District Court in the Southern District of Ohio in 2006 where the court determined that because the league had not concealed material information, the statute of limitations precluded the plaintiff’s claims.[57] This decision was later affirmed by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in 2007.[58] The lawsuit aimed to recover as much as $200 million to offset the taxpayers’ liability, but serious questions about the integrity of the suit led to a decision in favor of the NFL and its clubs.[59]

The battle to recover taxpayer funds ensued when outraged County resident Carrie Davis brought suit alleging that the NFL had improperly pressured the City of Cincinnati and Hamilton County into greenlighting the Bengals’ new stadium.[53] In the suit, Plaintiff Davis alleged that “[t]he NFL violated federal anti-trust provisions by using its monopoly to extort new stadiums at highly favorable lease terms from communities. . . .[t]he bottom line is the NFL lied not just to . . . County residents but to numerous communities across the country to make taxpayers fund a private enterprise.”[54] The original lawsuit before the Hamilton County Common Pleas Court named the Bengals and all thirty-one other NFL franchises, accusing them of fraud, civil conspiracy, antitrust violations, and breach of contract.[55] Later in 2004, U.S. District Judge S. Arthur Spiegel determined that the County did have legal standing to bring the case, dismissing the arguments from the NFL.[56] The case was later brought before the District Court in the Southern District of Ohio in 2006 where the court determined that because the league had not concealed material information, the statute of limitations precluded the plaintiff’s claims.[57] This decision was later affirmed by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in 2007.[58] The lawsuit aimed to recover as much as $200 million to offset the taxpayers’ liability, but serious questions about the integrity of the suit led to a decision in favor of the NFL and its clubs.[59]

The crux of the case surrounded the statute of limitations. The County argued that because of fraudulent representations by the Bengals, the statute of limitations should have begun on a date other than when the original Lease was signed, allowing the County to bring an antitrust claim against the Bengals.[60] The Sixth Circuit requires antitrust plaintiffs to “demonstrate wrongful, ‘affirmative acts of concealment’” in order to prevail, and the District Court determined that there were “simply no affirmative representations to satisfy this requirement.”[61] Moreover, because the County had knowledge of possible antitrust violations at the time of signing, and because the County failed to exercise due diligence in investigating the matter, there was no legal recourse available to Hamilton County as the statute of limitations had run.[62] Judge Spiegel summarizes his holding in the concluding paragraph of the decision:

To be sure, the lease that Hamilton County enjoys with the Bengals is highly favorable—perhaps egregiously so—to the Bengals. It may well be that the Hamilton County taxpayers are not enjoying benefits concomitant with their investment in Paul Brown Stadium and in the Bengals’ franchise. It may even be that this lease was the consequence of unlawful anticompetitive behavior by the Bengals and the NFL. Despite these truths—if they be truths—this Board cannot advance stale claims. Whether for good or ill, prior members of the Board negotiated the instant lease with the Bengals fully aware of the possibility that the team and the NFL allegedly wielded unlawful antitrust power to obtain favorable terms under the lease. They simply failed to object or to otherwise advance a claim on behalf of Hamilton County taxpayers until it was lost to the passage of time. It should be abundantly clear that the Court’s dismissal of Plaintiff’s claims is strictly on the question of the statute of limitations and is in no way a decision on the merits of Plaintiff’s substantive causes of action under anti-trust law.[63]

At the end of 2010, the Hamilton County Commission voted 2-1 for a deal to mitigate $16 million in projected lsses for the fiscal year 2011 stemming from the Reds and Bengals stadiums, despite both leases exempting the teams from rent payments from 2011-2015.[64] The emergency agreement included provisions for the Bengals to pay $7.4 million in rent for Paul Brown Stadium over the next five years, and for the Reds to pay $2.2 million for Great American Ball Park.[65] Bengals spokesman, Inky Moore, stated that “[t]he Bengals hope that [the rent agreement] will serve the public interest by helping to stabilize the county’s financial picture. . .”[66] Further, the Bengals agreed to contribute $150,000 per year in revenue from the hosting of non-sports events.[67] Moreover, the County agreed to reduce a property tax rollback that was included in the original package to increase commitments for the Cincinnati stadium projects.[68] The original tax reduction failed to generate the necessary revenue to fund the stadiums and only increased the burden on Cincinnati taxpayers.[69]

At the end of 2010, the Hamilton County Commission voted 2-1 for a deal to mitigate $16 million in projected lsses for the fiscal year 2011 stemming from the Reds and Bengals stadiums, despite both leases exempting the teams from rent payments from 2011-2015.[64] The emergency agreement included provisions for the Bengals to pay $7.4 million in rent for Paul Brown Stadium over the next five years, and for the Reds to pay $2.2 million for Great American Ball Park.[65] Bengals spokesman, Inky Moore, stated that “[t]he Bengals hope that [the rent agreement] will serve the public interest by helping to stabilize the county’s financial picture. . .”[66] Further, the Bengals agreed to contribute $150,000 per year in revenue from the hosting of non-sports events.[67] Moreover, the County agreed to reduce a property tax rollback that was included in the original package to increase commitments for the Cincinnati stadium projects.[68] The original tax reduction failed to generate the necessary revenue to fund the stadiums and only increased the burden on Cincinnati taxpayers.[69]

The public funding crisis continued into 2012 as mounting debt from the new facility[70] caused the County to sell off a public hospital in order to balance its failing budget. [71] Dusty Rhodes, the County Auditor, went so far as to describe the budget balancing practices as “basically a fire-sale.”[72] Again in 2014, the County paid out $50 million for debt service attributed to the Bengals and Reds’ stadiums.[73]

E. Worst Stadium Deal of All Time?

In the wake of this massive public expenditure, Hamilton County officials continue to justify their contribution. County Commissioner Chris Monzel offers a weak justification in a quote from 2016. “Is it worth it? I don’t know. My gut says that it probably hasn’t generated the rate of return on investment that other projects do. From a civic pride standpoint, people are excited about [the Bengals]. You’ve got some intangibles that you can’t really put a price tag on.”[74]

In the wake of this massive public expenditure, Hamilton County officials continue to justify their contribution. County Commissioner Chris Monzel offers a weak justification in a quote from 2016. “Is it worth it? I don’t know. My gut says that it probably hasn’t generated the rate of return on investment that other projects do. From a civic pride standpoint, people are excited about [the Bengals]. You’ve got some intangibles that you can’t really put a price tag on.”[74]

‘Intangibles’ are hardly enough to defend the massive public spending blunder on publicly financed stadiums. The Bengals and the County were both given blistering reviews of their performance on the stadium development project, but the Bengals felt that they were judged unfairly.[75] While the Cincinnati project has been labeled “the Worst Stadium Deal Ever,” there was a wave of relief for the taxpayers attributed to rapidly decreasing yields from municipal bonds.[76] In 2016, yields for these municipal bonds dropped to their lowest level over return since 1961, and County officials were able to refinance $376 million in municipal bond debt, that will save the County an estimated $87 million through 2032.[77] County Commissioner Monzel blames the effect of the recession and stagnant sales tax revenues for the ballooning costs to the public.[78]

Pro-sports subsidies exceeded the $23.6 million that the county cut from health-and-human-services spending in the current two-year budget (and represent a sizable chunk of the $119 million cut from Hamilton County schools). Press materials distributed by the Bengals declare that the team gives back about $1 million annually to Ohio community groups. Sound generous? That’s about 4 percent of the public subsidy the Bengals receive annually from Ohio taxpayers.[79]

While there are certainly legitimate reasons for ballooning costs and budget overruns, the contractual mechanisms employed in the Lease did little or nothing to protect the interests of the taxpayers, and did a great deal to enrich the Bengals. If taxpayers and County officials in 1996 knew they would be paying down debt for a stadium project through 2030, the voting calculus likely would have been different.

III. Budget Overruns Are Commonplace

Budget overruns are a concern to any major construction project, but for those primarily funded by public entities, the negative effects are only exacerbated when scrutinized in the public eye. Martin J. Greenberg discusses the many challenges of securing financing for sports facilities in a symposium published in the Marquette Sports Law Review entitled Sports Facility Financing and Development Trends in the United States.

Budget overruns are a concern to any major construction project, but for those primarily funded by public entities, the negative effects are only exacerbated when scrutinized in the public eye. Martin J. Greenberg discusses the many challenges of securing financing for sports facilities in a symposium published in the Marquette Sports Law Review entitled Sports Facility Financing and Development Trends in the United States.

Obtaining approval for a sports facility financing plan is difficult at best. Every community that has constructed or renovated a sports facility has witnessed the acrimony. Debate rages amongst politicians, team owners, economists, media, and the general public . . . Teams focus most of their efforts on obtaining approval of the financing plan.[80]

Because of the large financial obligation necessary to construct a sports facility, it is very difficult to secure financing. The “age-old” model for securing a financing plan for sports facilities has included an investment from the taxpayers. Teams are able to put immense amounts of pressure on municipalities and often secure public financing plans that are extremely favorable to their own interests. This poses a large problem for legislators trying to maintain public support for financing professional sports. For instance, the construction of the $1.3 billion Yankee Stadium, for the fourth most valuable sports franchise in the world, [81] still demanded a contribution from the taxpayers. [82] While the City’s original projected costs were only 95.5 million, the City of New York was eventually stuck with over $170 million dollars to replace public parklands that were demolished in favor of the new facility.[83] For public entiies that do decide to provide financial assistance for a stadium development, it is important that they are adequately protected from the unvisitable pitfall that is construction cost overrun.

The issue of overruns has arisen in the context of construction projects of stadiums and arenas over time. In 2001, the National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School, through its Sports Facility Reports, performed a survey of cost overruns including the amount of cost overruns, the cause, and the payment responsibility.

| Major Professional Sports Leagues Stadium Cost Overruns[84] |

|||||

| TEAM | STADIUM/ARENA | ORIGINAL ESTIMATE | COST OVERRUN | CAUSE | PAYMENT |

| Carolina Hurricanes | Entertainment & Sports Arena | $130M | $26M | Design changes requested by team and Centennial Authority, weather conditions | (1) $5.2M from Centennial Authority reserve fund; (2) $8M from team; (3) $6M from NC State University. |

| Cincinnati Bengals | Paul Brown Stadium | $287M (cost escalated to $458M before completion) | $51M | Changes from original plans, project delays, and additional expenses caused by weather conditions and land acquisition. | Poor record keeping is limiting city / county officials from seeking collection of more than $18.5M from the project construction manager. |

| Cleveland Browns | Cleveland Browns Stadium | $280M | $28M | Weather, additional construction costs. | Browns owner, Alfred Lerner, and city officials agreed to split the cost overruns exceeding $283M with a cap of $293M. |

| Cleveland Cavaliers | Gund Arena | $152M | $76M (combined cost overruns from Gund Arena project) | Construction costs. | Team agreed to pay $7M in disputed costs. |

| Cleveland Indians | Jacobs Field | $173M | $76M (combined cost overruns from Gund Arena project) | Construction costs. | NBA Cavs have agreed to pay $7M in disputed costs. |

| Houston Texans | Reliant Stadium | $310M | $57M | Taxpayers, through the Harris County-Houston Sports Authority, are responsible for cost overruns. | |

| Seattle Mariners | Safeco Field | $417M | $100M | Accelerated construction schedule, architectural flaws, and construction overruns. | Mariners have paid for all overruns. |

Likewise, a report from Charles Anderson, Commission Auditor of the Board of County Commissioners of Hamilton County, analyzed cost overruns as it relates to Great American Ballpark, Petco Park, and National Park. What follows are his findings:[85]

| Major League Baseball Stadium

Cost Overruns 2003 – Present

|

|||

| Stadiums | Great American Ballpark

(Cincinnati Oh) |

PETCO Park

(San Diego, CA) |

Nationals Park

(Washington, D.C.) |

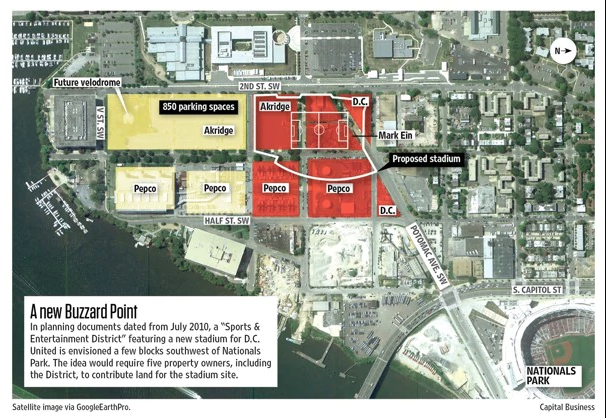

| Construction Company | Hunt Construction Group, Inc. (Indianapolis) | San Diego Ballpark Builders (a joint venture of Clark Construction Group Inc., Nielsen Dillingham Builders Inc. and Douglas E. Barnhart Inc.) | Hunt Construction Group in a joint venture Clark Construction and Smoot Construction |

| Architect | HOK Sport (Kansas City); and GBBN Architects (Cincinnati) | HOK Sport, Antoine Predock (design), Spurlock Poirier (landscape) and ROMA (urban planning). | HOK Sport (Kansas City) and Devrouax & Purnell Architects-Planners (Washington) |

| Construction Overruns | Great American Ballpark is part of an ongoing larger redevelopment project that includes the construction of the Paul Brown Football Stadium (opened 2000) for the Cincinnati Bengals, and the Central Riverfront Development. Technically, the Great American Ballpark did not go over budget. It cost $310 million with $280 from Hamilton County and $30 million from the Team in the form of three $10 million pre-completion payments made by the Team to the County. The County capped its cost at $280 million. The revenues from a ½ percent sales tax increase approved by the voters in 1996 funded the ballpark. The revenue from the sales tax was divided in the following manner: 30% went towards property tax rollback and 70% towards the riverfront which included the Great American Ballpark and the Paul Brown Stadium. The funding source, the ½ percent sales tax increase was to cover both the construction of the ballpark and football stadium; therefore, both projects are inherently connected. The Paul Brown Stadium was budgeted for $287 million (did not include the cost for land and roadwork) with a 1% contingency. The Paul Brown Stadium went over budget by $51 million, plus Hamilton County spent another $1 million in legal fees trying to recoup some funds. In addition, the land was originally budgeted for $40 million. It cost $70 million. | The final cost of the stadium facilities, according to most estimates, was $456.8 million. The Padres chipped in $153 million, 33.5% of the total cost. The other 66.5% – $303.8 million – came from public funds: $225 million from bonds, $21 million from the San Diego Unified Port District, and $57.8 million from the City’s redevelopment agency. The San Diego Center City Development Corporation ultimately contributed $7.8 million more than the $50 million originally provided for in the non-binding memorandum of Understanding (MOU). The details of this additional $7.8 million are unclear, despite the fact that the MOU stated that the Padres would be liable for cost overruns. The Padres did, however, provide $38 million of the $45.8 million overruns. | The original budget for the entire project was $630,800,000. The final cost was estimated to be $693 million. No construction overruns occurred. However, cost overruns did occur in acquiring the property and environment cleanup work was greater than expected. These overrun cost were covered by the District of Columbia |

| Overrun Safeguard

Provisions |

The budget for the Great American Ball Park was capped at $280 million, payable by Hamilton County. Any cost over the $280 million was covered by the Cincinnati Reds.

In addition, the Great American Ballpark was built after the Paul Brown Stadium; therefore, the County had learnt from that example and placed the $280 million cap. |

The Padres and Padres Construction, L.P. were be solely responsible for any and all design and construction costs for the Ballpark exceeding the Ballpark Estimate and amounts necessary to satisfy such excess are deposited into and paid from the Design and Construction Fund. | The Construction Administration Agreement provides that any excess of the total Project Cost over the initial Project Budget are borne by the District of Columbia Sports and Entertainment Commission, except changes that were requested by the team after the specifications have been approved. |

In January of 2010, Evolution Media Capital presented research on NFL Stadium Financing to Centre City Development Corporation in which the presentation document outlines the responsibility for cost overruns:[86]

In January of 2010, Evolution Media Capital presented research on NFL Stadium Financing to Centre City Development Corporation in which the presentation document outlines the responsibility for cost overruns:[86]

| Appendix A – Stadium Summary

Team Responsibilities |

||||||

| Franchises | Year Opened | Ownership | Responsible For Cost Overruns | Retain Revenues | Operating

Expenses |

Rent

(>$1M p.a.) |

| Detroit Lions | 2002 | X | X | Teams | ||

| Houston Texans | 2002 | X | X | Team | X | |

| New England Patriots | 2002 | X | X | X | Team | X |

| Seattle Seahawks | 2002 | X | X | Team | ||

| Chicago Bears | 2003 | X | X | Team | X | |

| Green Bay Packers | 2003 | X | X | Split | ||

| Philadelphia Eagles | 2003 | X | X | Split | X | |

| Arizona Cardinals | 2006 | X | Public | |||

| Indianapolis Colts | 2008 | X | X | Split | ||

| Dallas Cowboys | 2009 | X | X | Team | X | |

| Kansas City Chiefs | 2010 | X | X | Team |

Soldier Field: Chicago Bears

The renovation of Soldier Field in Chicago, Illinois, was pushed through by City officials in order to modernize the historic football stadium.[87] Soldier Field opened in 1924, and renovations changed the original ‘Colosseum-like’ structure to now resemble a futuristic, yet ‘broken flying saucer.’[88] Though the new design brought the venue up to NFL standards by adding triple the concession stands and double the restrooms of the old facility, stadium capacity was reduced more than 5,000 seats.[89]

The renovation of Soldier Field in Chicago, Illinois, was pushed through by City officials in order to modernize the historic football stadium.[87] Soldier Field opened in 1924, and renovations changed the original ‘Colosseum-like’ structure to now resemble a futuristic, yet ‘broken flying saucer.’[88] Though the new design brought the venue up to NFL standards by adding triple the concession stands and double the restrooms of the old facility, stadium capacity was reduced more than 5,000 seats.[89]

The development was estimated to cost $606 million, but with the final bill coming in closer to $655 million, the project collected a cost overrun of $49 million dollars.[90] Chicago Bears President Ted Phillips said that “the overruns included $18 million for asbestos removal and higher than expected costs for ‘sounder’ parking garages, Bears history-related displays and a retail store.”[91] The stadium renovation obligated the Bears to pay for any budget overruns, protecting the public investment and assuring that no more public money was allocated.[92] In financing the stadium development, Illinois Sports Facilities Authority contributed $406 million through taxpayer backed bonds, and the Bears and the NFL contributed an additional $200+ million.[93] However, years after the completion of the project, an analysis by the Chicago Tribune revealed that the total cost was closer to $690 million, with the public’s contribution of $432 million, rather than the intended $406 million.[94]

IV. Sample Provisions

What follows are some sample overrun provisions taken from sports venue leases, construction, and development agreements:

- Kansas City Royals[95] – (2006 LEASE AMENDMENT between JACKSON COUNTY SPORTS COMPLEX AUTHORITY and KANSAS CITY ROYALS BASEBALL CORPORATION)

- “(vi) Cost Overruns. Tenant shall be responsible for any cost overruns in connection with the Leased Premises Renovation.”

- Orlando City FC[96] – (ORLANDO SOCCER STADIUM PROJECT CONSTRUCTION AGREEMENT)

- “3 Cost Overruns. The Project Developer shall pay, or cause OSH to pay, all costs and expenses in connection with the design, construction, furnishing and equipping of the Project Improvements to the extent such costs and expenses exceed the Budget Cap, including any modifications requested by MLS to comply with MLS Facilities Standards or other of its rules and regulations, but excluding any costs or expenses which are Excluded Costs (the “Cost Overruns”). The City shall have no responsibility to pay any Cost Overruns, Excluded Costs or other costs which the Project Developer is otherwise obligated to pay pursuant to this Agreement.”

- Texas Rangers[97] – (MASTER AGREEMENT REGARDING BALLPARK COMPLEX PROJECT between CITY OF ARLINGTON and RANGERS BASEBALL LLC)

- “Section 3.2. Project Budget and Master Plan

(c) The Ballpark Complex Budget shall reflect the line items set forth on the attached Exhibit D and no material change shall be made by the Team in the Ballpark Complex Budget unless (i) such change is disclosed to the City, (ii) such change does not affect the suitability of the Ballpark Complex as a Major League Baseball venue, and (iii) to the extent such change causes the Project Costs to exceed $1,000,000,000 (One Billion Dollars), the Team, subject to the Team’s acceptance of the revised Ballpark Complex Budget, shall be responsible for any such Cost Overruns as an Additional Cost; provided, however, the Project Documents will further detail the required completion standards resulting from the Team’s change orders as elected by the Team.”

- Minnesota Vikings[98] – (CONSTRUCTION SERVICES AGREEMENT between THE MINNESOTA SPORTS FACILITIES AUTHORITY and THE CONSTRUCTION MANAGER)

- ARTICLE 3 – AUTHORITY’S RESPONSIBILITIES (3.9) “The Authority and Indemnitees are relying on the Construction Manager’s GMP, which contains a Construction Manager Contingency as provided in Exhibit 3 to the Construction Services Agreement, to pay for all Costs of the Work and Claims for additional payment (other than for approved Contract Revisions) above the GMP. The Act permits the Authority to enter into this Construction Services Agreement only on the express condition that the Construction Manager is responsible for cost overruns above the GMP; as a result, the Construction Manager shall be responsible to pay all Costs of the Work and other costs or expenses that exceed the GMP. The Authority and Indemnitees (except the Architect Indemnitees with respect to design errors or omissions or breaches of the Design Services Agreement) are not, and shall in no event be, responsible or liable to any member of the Project Team including the Construction Manager for any aspect of the Design Services, including inspections, quality control or design administration services that will be provided by the Architect under its Design Services Agreement, other than as provided in Paragraph 4.3 herein. Likewise, the Authority and the Indemnitees (except the Architect Indemnitees with respect to design errors or omissions or breaches of the Design Services Agreement) are not and shall in no event be, responsible or liable to the Construction Manager or other Project Team members for any Claims for payment of additional money or costs above the GMP arising out of or related to any aspect of the Construction Manager’s performance of the Work, except with respect to the Authority’s obligations under Paragraph 3.4 of Exhibit 6 hereto. In no event shall the Authority or Indemnitees have any responsibility or liability for construction means, methods, techniques, sequences, or procedures, or for safety precautions and programs in connection with the Work, notwithstanding any of the rights and authority granted the Authority and Indemnitees in the Contract Documents.

- Atlanta Braves[99] – (DEVELOPMENT AGREEMENT between COBB-MARIETTA COLISEUM AND EXHIBIT HALL AUTHORITY and ATLANTA NATIONAL LEAGUE BASEBALL CLUB, INC.)

- “Article 6 – Financing and Funding of the Project

6.5 Cost Overruns. The Braves Parties shall be responsible for payment of any Cost Overrun, which payment shall be made upon demand by the County or at such earlier time as may be necessary to ensure the payment or performance, as the case may be, of the subject task or expense itemized in the Stadium project Budget within the applicable, timeframe contained in the Stadium Construction Documents, including the Project Milestone Schedule. So long as the Braves Parties are diligently proceeding to complete the Stadium in accordance with the Contract Documents (including the Project Milestone Schedule), the County shall not incur costs for which the County shall not be liable or to obligate the Braves Parties to incur costs without the prior written approval of the Braves Parties.”

V. More Recent Examples

A. US Bank Stadium: Minnesota Vikings

The new home of the Minnesota Vikings (Vikings), U.S. Bank Stadium, opened in July of 2016 in the Downtown East section of Minneapolis.[100] The new facility had an approximate construction cost of $1.027 billion, and more than half of the stadium cost will be paid using private funds.[101] The public’s portion–approximately 46% percent or $498 million–will be funded through tax revenues from pulltabs and other charitable gambling, as well as increased sales taxes in the City of Minneapolis.[102]

The new home of the Minnesota Vikings (Vikings), U.S. Bank Stadium, opened in July of 2016 in the Downtown East section of Minneapolis.[100] The new facility had an approximate construction cost of $1.027 billion, and more than half of the stadium cost will be paid using private funds.[101] The public’s portion–approximately 46% percent or $498 million–will be funded through tax revenues from pulltabs and other charitable gambling, as well as increased sales taxes in the City of Minneapolis.[102]

Greenberg and Michael Gavin break down the three major public sources of funding for US Bank Stadium in their article entitled The Windfall Clause:[103]

- City of Minneapolis – $150 Million: The City’s contribution will be paid to the Minnesota Sports Facility Authority (“MSFA” or “The Authority”) by issuing appropriation bonds, and those bonds will be repaid to the “State by redirecting a portion of the current ‘Convention Center Taxes.’”[104]

- State of Minnesota – $348 Million: The State issued appropriation bonds valued at $462 million and the remaining of the $498 million public contribution will be paid for by State funds.[105]

- Public Contribution Remainder: “The remaining amount of the appropriation bonds will be repaid to the bondholders from other sources available to the state, including the modernization of state-authorized charitable gaming that includes electronic pull-tabs and bingo and a one-time inventory tax on cigarettes, which raised approximately $36 million.”[106]

The Construction Services Agreement signed February 15, 2013 between the Minnesota Sports Facility Authority (“MSFA”) and Mortenson Construction (the “Construction Manager”) was drafted to ensure that MFSA would not be obligated to pay for any cost overruns associated with the completion of the Stadium Project. Article 5 of the Constructions Services Agreement defines Mortenson’s obligation to prepare a report that includes a Guaranteed Maximum Price (“GMP”). The GMP figure was critical to the preparation of the stadium plans, as Mortenson would be responsible for any costs above the GMP. However, the GMP was not finalized at the time the Agreement was signed, leaving a large financial vulnerability for all parties involved. This is an example of where so-called “agreements to agree” can be very dangerous when public tax dollars are involved.

The Construction Services Agreement signed February 15, 2013 between the Minnesota Sports Facility Authority (“MSFA”) and Mortenson Construction (the “Construction Manager”) was drafted to ensure that MFSA would not be obligated to pay for any cost overruns associated with the completion of the Stadium Project. Article 5 of the Constructions Services Agreement defines Mortenson’s obligation to prepare a report that includes a Guaranteed Maximum Price (“GMP”). The GMP figure was critical to the preparation of the stadium plans, as Mortenson would be responsible for any costs above the GMP. However, the GMP was not finalized at the time the Agreement was signed, leaving a large financial vulnerability for all parties involved. This is an example of where so-called “agreements to agree” can be very dangerous when public tax dollars are involved.

The Development Agreement signed October 3, 2013 between the MFSA and the Vikings was also drafted to protect the public from cost overruns. The relevant portions relating to cost overruns from the Construction Services Agreement and the Development Agreement are included below:

- (Development Agreement – Section 8.8)[107]

- Section 8.8 Cost Overruns: The Stadium Developer shall be responsible for payment of any Cost Overrun, which payment shall be made at such time as any portion thereof is legally required to be paid with respect to the Project; provided, however, that if the Stadium Developer is the Authority, the contract or contracts entered into by the Authority under Article 6 hereof shall provide that any Cost Overruns are the responsibility of the Construction Manager, trade contractor or vendor, and not of the Authority or the State; and provided, further, in no event shall the State or the Authority be liable to contribute in excess of Four Hundred Ninety-Eight Million Dollars ($498.0 million) for Project Costs. The Authority shall not accept responsibility for Cost Overrun and shall not be responsible for Cost Overruns if the Authority has authorized the Team to become the Stadium Developer under Section 6.1, in which case the Team shall be responsible for Cost Overruns.[108]

- (Development Agreement – Section 6.1)[109] Section 6.1 Stadium Developer.

- (a) Role of Stadium Developer. Except as set forth in Section 6.1(b) below, the Authority shall serve as the Stadium Developer. The Stadium Developer will be responsible for, among other things, the stewardship of the Project Funds and the public interest therein, observing public bidding methods where required or practicable, coordinating regulatory approvals with applicable Governmental Authorities, providing the highest degree of transparency regarding all contractual and funding arrangements, complying with government data practices requirements, implementing and enforcing the Construction Services Agreement Equity Plan (as defined in the Construction Services Agreement), ensuring the Construction Manager’s execution of an appropriate Project Labor Agreement, and cooperating with audit and oversight procedures of the Legislative Auditor and the Legislative Commission on Minnesota Sports Facilities.

- (b) Team Assumption of Stadium Developer Duties. Prior to the Certification of GMP by the Construction Manager, the Team may request to become the Stadium Developer as provided in Section 473J.11, subd. 1(f) of the Act. To become the Stadium Developer, the Team must agree to assume the roles and responsibilities of the Authority as the Stadium Developer for completion of construction in a manner consistent with the Effective Date Minimum Design Standards and, after Certification of GMP, the Final Minimum Design Standards and agreed upon Contract Documents, and any other applicable construction-related roles and responsibilities of the Authority as the Stadium Developer under the Act, including, without limitation, responsibility for Cost Overruns.

- (Construction Services Agreement –3.9)[110]

- Authorities and Indemnitees are relying on the Construction Manager’s GMP, which contains a Construction Manager Contingency as provided in Exhibit 3 to the Construction Services Agreement, to pay for all Costs of the Work and Claims for additional payment (other than for approved Contract Revisions) above the GMP. The Act permits the Authority to enter into this Construction Services Agreement only on the express condition that the Construction Manager is responsible for cost overruns above the GMP; as a result the Construction Manager shall be responsible to pay all Costs of the Work and other costs or expenses that exceed the GMP. The Authority and Indemnitees (except the Architect Indemnitees with respect to design errors or omissions or breaches of the Design Services Agreement) are not, and shall in no event be, responsible or liable to any member of the Project Team including the Construction Manager for any aspect of the Design Services, including inspections, quality control or design administration services that will be provided by the Architect under its Design Services Agreement, other than as provided in Paragraph 4.3 herein. Likewise, the Authority and the Indemnitees (except the Architect Indemnitees with respect to design error or omissions or breaches of the Design Services Agreement) are not and shall in no event be, responsible or liable to the Construction Manager or other Project Team members for any Claims for payment of additional money or costs above the GMP arising out of or related to any aspect of the Construction Manager’s performance of the work, except with respect to the Authority’s obligations under Paragraph 3.4 of Exhibit 6 here to.

- (Construction Services Agreement – Sec. 1 Guaranteed Maximum Price [GMP])[111]

- 1.1 As part of its Pre-Construction Phase Services described in Exhibit 1 hereto, the Construction Manager will be asked to prepare a Construction Management Plan including a GMP Proposal for the Work and a Construction Schedule based on the GMP Pricing Documents. If the Construction Management Plan is acceptable to the Authority and Team, which decision shall be in their sole discretion, then the Construction Manager’s Construction Management Plan shall be added to this Construction Services Agreement as a Contract Revision in the form of a completed Exhibit 3 hereto. The Authority may require that the GMP be separated into two or more separate sums and be tracked separately throughout the course of the Work.

- 1.4 By virtue of providing the GMP, the Construction Manager shall, as required by the Act, accept the risk of cost overruns in excess of the GMP, as modified in accordance with and allowed by the Contract Documents, and such cost overruns shall not be the responsibility of the Authority, State, or Team.

- (Construction Services Agreement – Section 17.3.3)[112]

- Construction Manager agrees and acknowledges that the Act requires the Authority to bid project construction in a manner that any cost overruns that exceed the GMP are the responsibility of the successful bidder and not the Authority or the State. Accordingly, Construction Manager agrees and acknowledges that as the successful bidder, Construction Manager is solely responsible for any cost overruns that may occur on the Project in excess of the GMP as modified in accordance with and as allowed by the Contract Documents, however caused, as the Authority has no authority to accept liability for cost overruns in contravention of the Act. Therefore, notwithstanding anything to the contrary in this Construction Services Agreement except as provided in Paragraph 4.3 hereof and Subparagraph 10.3.1 of Exhibit 6 hereto, to the fullest extent permitted by Applicable Law, Construction Manager hereby waives any and all Claims against Authority and any of the Indemnitees (except the Architect Indemnitees) arising from or relating to (1) the Architect’s negligent acts, errors or omissions; (2) any implied or express warranty as to the completeness, constructability, accuracy, suitability, or timeliness of the completion of any Drawings, Specifications, or other Contract Documents; and (3) any other Claim the result of which would be to impose liability upon the Authority for a cost overrun in violation of the Act . . .

The construction of US Bank Stadium offers a prime example of how taxpayers become obligated to pay the unforeseeable costs associated with major construction projects. Estimating the actual costs and potential project delays for a major stadium project is a nearly impossible feat. Authority Chair of the MSFA Michele Kelm-Helgen expressed her frustrations saying, “[i]t’s a very complicated, multi-partner agreement that has current and future costs that had to be estimated.”[113] The $1.1 billion dollar venture amassed a final budget overrun cost of $16.25 million after multiple instances of change orders and unintended setbacks.[114] In February of 2016, a leak in the new facility cost Mortenson between $3 and $4 million dollars to repair.[115] Another instance saw a pedestrian service bridge originally estimated at a cost of $9.6 million increase to $10.6 million associated with cost adjustments and change orders.[116]

The construction of US Bank Stadium offers a prime example of how taxpayers become obligated to pay the unforeseeable costs associated with major construction projects. Estimating the actual costs and potential project delays for a major stadium project is a nearly impossible feat. Authority Chair of the MSFA Michele Kelm-Helgen expressed her frustrations saying, “[i]t’s a very complicated, multi-partner agreement that has current and future costs that had to be estimated.”[113] The $1.1 billion dollar venture amassed a final budget overrun cost of $16.25 million after multiple instances of change orders and unintended setbacks.[114] In February of 2016, a leak in the new facility cost Mortenson between $3 and $4 million dollars to repair.[115] Another instance saw a pedestrian service bridge originally estimated at a cost of $9.6 million increase to $10.6 million associated with cost adjustments and change orders.[116]

It is important to note, that while Mortenson would be responsible for any cost overruns, the Construction Services Agreement stipulated that MFSA would be solely responsible for any deviations from the original stadium plan, and for any change orders or purchases made directly by the MFSA. Upon the stadium’s completion, Mortenson claimed that the MFSA should be responsible for paying the $15 million in disputed costs, $14 million of which would be the responsibility of subcontractors who had completed their work.[117] A spokesman for the Construction Manager stated that the dispute revolved around “[t]he cost and extra time related to changed and extra work directed by the MSFA after the final design documents were given to Mortenson.”[118]

In resolving the cost overruns for US Bank Stadium, MFSA reached a settlement agreement that moved $16.5 million dollars from the project contingency fund to cover the budget overrun.[119] The Vikings agreed to contribute another $5.5 million to compensate for their role in pushing upgrades to the facility plan.[120] It was imperative to MFSA and its constituents that the original agreement was honored so that no additional taxpayer money was allocated.[121] Mortenson did not eventually bear the burden of the cost overrun, and MFSA was able to settle the dispute by utilizing the $30 million dollar contingency fund.[122] While this did protect the public investment, the result proved disappointing as Mortenson had set the original GMP in order to avoid the MFSA having to access reserve fund.[123] Interested parties must ensure their understanding of contractual provisions that provide for financial obligations before they pledge a commitment to a major stadium project.

B. Mercedes-Benz Stadium: Atlanta Falcons/Atlanta United F.C.

| Stadiums that have opened since 2009 are heavily privately funded: (cost in millions)[1] | ||||

| Stadium | Year | Total Cost | Private Funding | Public Funding |

| Cowboys Stadium – Dallas Cowboys | 2009 | $1,194.0 | $750.0/63% | $444.0/37% |

| MetLife Stadium – New York Giants/Jets | 2010 | $1,600.0 | $1,600.0/100% | $000.0/0% |

| San Francisco 49ers | 2015 | $987.0 | $873.0/88% | $114.0/12 |

Cost overruns have proven to be a problem for taxpayer funded stadiums, but the same holds true for privately funded stadiums as well. Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta, Georgia, marks the continuation of a trend where a greater infusion of private capital is being thrust into the stadium equation.[124] Owners are contributing a larger portion toward stadium development costs and the NFL is helping those owners through the G4 Loan program, and fans are helping to fund their new stadium by purchasing personal seat licenses.[125]

In the construction of their projected $1 billion-dollar facility, the Atlanta Falcons (through the Atlanta Falcons Stadium Company, LLC—a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Falcons) will bear the burden of any cost overruns.[126] The Project Development and Funding Agreement (the “Agreement”) was signed between the Georgia World Congress Center Authority (“GWCCA”), the Atlanta Falcons Stadium Company (“StadCo”), and the Atlanta Falcons Football Club, and included provisions to shield taxpayers from construction cost overruns.[127] Section 7.8 of the Agreement sets forth the responsibility of StadCo to pay for any construction cost overruns associated with the New Stadium Project (“NSP”).[128]

In the construction of their projected $1 billion-dollar facility, the Atlanta Falcons (through the Atlanta Falcons Stadium Company, LLC—a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Falcons) will bear the burden of any cost overruns.[126] The Project Development and Funding Agreement (the “Agreement”) was signed between the Georgia World Congress Center Authority (“GWCCA”), the Atlanta Falcons Stadium Company (“StadCo”), and the Atlanta Falcons Football Club, and included provisions to shield taxpayers from construction cost overruns.[127] Section 7.8 of the Agreement sets forth the responsibility of StadCo to pay for any construction cost overruns associated with the New Stadium Project (“NSP”).[128]

Section 7.8 NSP Cost Overruns

(a) If any NSP Costs are incurred after the funds in the GWCCA NSP Cost Account are completely depleted (the “NSP Cost Overruns”), StadCo will be solely responsible for and will promptly pay or contribute to the StadCo NSP Cost Account (unless deposited directly into the Disbursement Account as provided in Section 7.4 above) as necessary cash in an amount equal to such NSP Cost Overruns. However, any amounts thereafter deposited into the Seat Rights Sales Account will be immediately disbursed to StadCo as reimbursement for its funding (if and to the extent so funded by StadCo) of any portion of the Public Contribution.

(b) The GWCCA will have the right to review and comment on and will have final approval rights with respect to any NSP Cost Overruns that exceed StadCo’s demonstrated financing capacity.[129]

The Agreement protects the taxpayers from footing any construction cost overruns associated with the construction of the ‘most complex roof ever built,’ or any other parts of the project.[130] In order to honor the promises of outspoken owner Arthur Blank that the stadium would be ready for the 2017 NFL season, the Falcons have accelerated the construction timeline causing a potential $400 million in cost overruns.[131] Tim Tucker of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution stated that delays stemmed from two signature features, “[a]n eight-piece retractable roof . . . and a 58-foot-high oval video board incorporated into the roof opening.”[132] Blank confirmed that “challenges in completing the design of the steel structure for the roof and video board . . . are the primary factors in revising the [June 1, 2017] target date for completion [of the stadium]. . .[133]

As of June 2016, Blank remained committed to meeting the July of 2017 opening date, which required further acceleration of the construction timeline by ‘compressing’ the schedule, which would result in ‘double-time, triple-time work.’[134] The stadium was originally scheduled to open on March 1, 2017, but after extensive delays and change orders the date was extended to June 1.[135] The opening was later delayed again to July 30, 2017, in order to host Major League Soccer (“MLS”) club Atlanta United’s first game in Mercedes-Benz Stadium.[136] In April of 2017, the stadium was delayed again, unable to meet the original commitment.[137] Steve Cannon, CEO of AMB Group (the parent company of the Atlanta Falcons) announced that the opening of the stadium would be further delayed until August 26, 2017, in order to accommodate the Falcons pre-season football schedule.[138] The latest round of delays was caused by complicated steel work on the roof that was taking ‘longer than anticipated.’[139] This scheduling snafu led Atlanta United’s MLS’s match to be relocated to Georgia Tech’s Bobby Dodd Stadium on July 29th, 2017, and two other United matches to be rescheduled.[140] Atlanta United President Darren Eales expressed his understanding of fans’ disappointment, but remained positive that the new stadium would ‘delight’ the Atlanta United fan base.[141]

As of June 2016, Blank remained committed to meeting the July of 2017 opening date, which required further acceleration of the construction timeline by ‘compressing’ the schedule, which would result in ‘double-time, triple-time work.’[134] The stadium was originally scheduled to open on March 1, 2017, but after extensive delays and change orders the date was extended to June 1.[135] The opening was later delayed again to July 30, 2017, in order to host Major League Soccer (“MLS”) club Atlanta United’s first game in Mercedes-Benz Stadium.[136] In April of 2017, the stadium was delayed again, unable to meet the original commitment.[137] Steve Cannon, CEO of AMB Group (the parent company of the Atlanta Falcons) announced that the opening of the stadium would be further delayed until August 26, 2017, in order to accommodate the Falcons pre-season football schedule.[138] The latest round of delays was caused by complicated steel work on the roof that was taking ‘longer than anticipated.’[139] This scheduling snafu led Atlanta United’s MLS’s match to be relocated to Georgia Tech’s Bobby Dodd Stadium on July 29th, 2017, and two other United matches to be rescheduled.[140] Atlanta United President Darren Eales expressed his understanding of fans’ disappointment, but remained positive that the new stadium would ‘delight’ the Atlanta United fan base.[141]

Though Blank and the Falcons are funding the billion-plus dollar endeavor, cost overruns are an ever-present obstacle to the timely and budget-friendly completion of sports venues. As of June of 2016, the Falcons had already ordered over $200 million in changes, which will likely bring the final expenditure of the stadium closer to $2 billion rather than the original estimate of $1 billion.[142] Over a year later in July of 2017, costs have risen to $1.6 billion on the unfinished stadium, yet Falcons General Manager Scott Jenkins reassured the public that the project would be completed by August 26, 2017.[143] Again, it is evident that deadlines have an overbearing impact on construction projects and are a significant contributor to cost overruns.

C. New Arena Replacing The Bradley Center: Milwaukee Bucks

As construction of the Milwaukee Bucks’ new facility progresses into 2017, [144] Milwaukeeans are buzzing about the future of the NBA in southeastern Wisconsin. [145] The project was funded by a partnership between the City and County of Milwaukee, the Wisconsin Center District (“District”), the State of Wisconsin, and the Milwaukee Bucks.[146] More specifically, the first half of the stadium project will be financed through a $250 million dollar contribution from the taxpayers, and the second half through a $150 million contribution from team owners Wes Edens, Marc Lasry, and Jamie Dinan, and a $100 million dollar gift from former owner and U.S. senator, Herb Kohl.[147] Financing the public’s contribution for the $500+ million endeavor was contingent upon securing the team for the foreseeable future. Part of the approved legislation and as a quid pro quo for dedicating public money to the arena project, [148] the Bucks were required to enter into a Non-Relocation Agreement with the District promising to utilize the new arena to be constructed as the exclusive venue for home games for the Bucks, and not to relocate the team. [149]

As construction of the Milwaukee Bucks’ new facility progresses into 2017, [144] Milwaukeeans are buzzing about the future of the NBA in southeastern Wisconsin. [145] The project was funded by a partnership between the City and County of Milwaukee, the Wisconsin Center District (“District”), the State of Wisconsin, and the Milwaukee Bucks.[146] More specifically, the first half of the stadium project will be financed through a $250 million dollar contribution from the taxpayers, and the second half through a $150 million contribution from team owners Wes Edens, Marc Lasry, and Jamie Dinan, and a $100 million dollar gift from former owner and U.S. senator, Herb Kohl.[147] Financing the public’s contribution for the $500+ million endeavor was contingent upon securing the team for the foreseeable future. Part of the approved legislation and as a quid pro quo for dedicating public money to the arena project, [148] the Bucks were required to enter into a Non-Relocation Agreement with the District promising to utilize the new arena to be constructed as the exclusive venue for home games for the Bucks, and not to relocate the team. [149]

Included in the Arena Finance, Funding and Construction Funds Escrow Agreement (the “Finance Agreement”) was a provision that any cost overruns during the construction of the new facility would the responsibility of the Bucks, not the taxpayers.[150] Bearing the cost of construction overruns would pose a significant possibility that Wisconsin taxpayers would foot the bill for any structural shortfalls, delays to scheduled construction, and other unforeseen circumstances during the process–on top of the original $250 million dollar investment.[151] Even though the public’s contribution is capped at $250 million, given the interest factor, the long-term cost of the arena financing from the City, State, County and District could rise to $400 million in taxpayer dollars over the next 20 years.[152]

Included in the Arena Finance, Funding and Construction Funds Escrow Agreement (the “Finance Agreement”) was a provision that any cost overruns during the construction of the new facility would the responsibility of the Bucks, not the taxpayers.[150] Bearing the cost of construction overruns would pose a significant possibility that Wisconsin taxpayers would foot the bill for any structural shortfalls, delays to scheduled construction, and other unforeseen circumstances during the process–on top of the original $250 million dollar investment.[151] Even though the public’s contribution is capped at $250 million, given the interest factor, the long-term cost of the arena financing from the City, State, County and District could rise to $400 million in taxpayer dollars over the next 20 years.[152]

By capping the amount of public borrowing for the arena, state officials are hoping to prevent taxpayers from picking up any cost overruns.[153] Former Bucks Vice President of Communications and Broadcast, Jake Suski, acknowledged that the Bucks would cover the cost of any budget overruns and stated that the Bucks, “[don’t] intend to have any cost overruns but we fully understand we’re assuming the risk in order to protect taxpayers.”[154] The Overrun Clause for the Milwaukee Bucks new arena is contained in the Arena Finance, Funding and Construction Funds Escrow Agreement (the “Finance Agreement”) made and entered into as of April 13, 2016 (the “Effective Date”) among the Wisconsin Center District (the “District”), the City of Milwaukee (the “City”), Deer District, LLC (“ArenaCo”), and First American Title Insurance Company (the “Escrow Agent).[155] Section 2 of the Finance Agreement addresses the allocation of the $250 million public commitment (the “District Commitment” plus the “City Commitment”):

- Allocation of Project Costs. The total Project Costs to complete the Arena and the Parking Facilitates are currently estimated at $524,000,000. Subject to the terms of this agreement, the City Disbursement Agreement, the Contribution Agreement and the Pledge Agreement: (a) the District shall pay for $203,000,000 of Project Costs for the Work (the “District Commitment”); (b) the City shall pay for (i) $35,000,000 of Project Costs for the Parking Facilities Work, and (ii) $12,000,000 of Project Costs for the Work related to the Public Plaza (collectively, the “City Commitment”); provided, however, if actual final Project Costs for the Parking Facilities Work of the Work related to the Public Plaza are less than these amounts, the remainder may be used as provided in the City Development Agreement; (c) the District shall use the Kohl Commitment received by the District pursuant to the Contribution Agreement and as a result of the Pledge Agreement to pay for $100,000,000 (net of any GMF Reimbursed Amount paid by the District and without taking into account any default interest paid with respect to the Kohl Commitment as set forth in Section 7.2.3) of Permitted Arena Costs; and (d) ArenaCo shall pay or cause to be paid for all Project Costs that exceed the District Commitment, the City Commitment and the Kohl Commitment (the “ArenaCo Commitment”). The ArenaCo Commitment is currently estimated to be at least $174,000,000. For the avoidance of doubt, the aggregate ofthe District Commitment, the City Commitment, and the Kohl Commitment (net of any GMF Reimbursed Amount paid by the District and without taking into account any default interest paid with respect to the Kohl Commitment as set forth in (Section 7.2.3) is the maximum amount of funds required to be contributed by the District (on its own behalf), the City and the District (solely as in its capacity of coordinating the disbursement of the Kohl Commitment hereunder), respectively, for Project Costs, without regard to whether total Project Costs exceed the estimate, but subject to Section 11.3 of the Development Agreement.[156]

The Overrun Clause, however, is subject to Section 11.3 of the Arena Development Agreement signed between Wisconsin Center District and Deer District LLC, the contents of which are included below.[157] Section 11.3 designates the obligations that arise from modifications to the construction work.[158] The City and District will be shielded from any cost overruns, except for such overruns that are a result of a Construction Work Modification request directly by the District.

The Overrun Clause, however, is subject to Section 11.3 of the Arena Development Agreement signed between Wisconsin Center District and Deer District LLC, the contents of which are included below.[157] Section 11.3 designates the obligations that arise from modifications to the construction work.[158] The City and District will be shielded from any cost overruns, except for such overruns that are a result of a Construction Work Modification request directly by the District.

11.3 Modifications to Construction Work. The Parties acknowledge that they may each desire to modify the Construction Documents and the scope of the Construction Work from time to time (a “Construction Work Modification”). Any Construction Work Modification shall be subject to the following provisions: