by Martin J. Greenberg and Aaron Davis

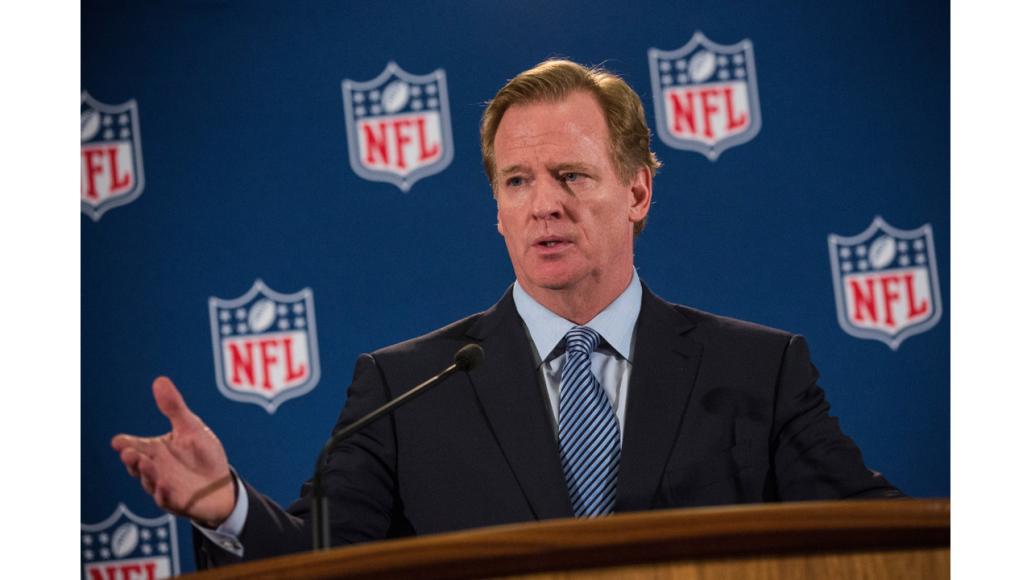

The National Football League (NFL) and its players have been plagued over the past several years with cases involving domestic violence, assault, child abuse, and other forms of family violence. The conduct of Ray Rice (Rice) and Adrian Peterson (Peterson) proved to be a massive blow to the image of the NFL in 2014. Although NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell (Goodell) had substantial discretionary authority in handling initial discipline cases, NFL owners and Goodell were aware that the NFL’s 2007 Personal Conduct Policy seemed ill-equipped in dealing with such novel player misconduct issues. In response, the NFL unilaterally revised their personal conduct policy to include a more extensive list of prohibited conduct.[1] Goodell faced heavy criticism for his handling of Rice’s domestic violence case, and after the policy’s revision in December of 2014, Goodell believed “The policy is comprehensive. It is strong. It is tough. And it [is] better for everyone associated with the NFL.”[2] Since the revision, NFL player arrests and citations beyond speeding tickets are at their lowest since 2000.[3] Although Goodell’s suspensions have been viewed by some to be “arbitrary” and an “abuse of discretion,” the new policy not only addresses these authoritative concerns, but further outlines the type of conduct that is detrimental to the NFL and professional football.[4]

The National Football League (NFL) and its players have been plagued over the past several years with cases involving domestic violence, assault, child abuse, and other forms of family violence. The conduct of Ray Rice (Rice) and Adrian Peterson (Peterson) proved to be a massive blow to the image of the NFL in 2014. Although NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell (Goodell) had substantial discretionary authority in handling initial discipline cases, NFL owners and Goodell were aware that the NFL’s 2007 Personal Conduct Policy seemed ill-equipped in dealing with such novel player misconduct issues. In response, the NFL unilaterally revised their personal conduct policy to include a more extensive list of prohibited conduct.[1] Goodell faced heavy criticism for his handling of Rice’s domestic violence case, and after the policy’s revision in December of 2014, Goodell believed “The policy is comprehensive. It is strong. It is tough. And it [is] better for everyone associated with the NFL.”[2] Since the revision, NFL player arrests and citations beyond speeding tickets are at their lowest since 2000.[3] Although Goodell’s suspensions have been viewed by some to be “arbitrary” and an “abuse of discretion,” the new policy not only addresses these authoritative concerns, but further outlines the type of conduct that is detrimental to the NFL and professional football.[4]

On February 19, 2014, a videotape surfaced of Rice’s involvement in a violent domestic dispute with his then-fiancée in a hotel elevator.[5] Rice was indicted on aggravated assault charges a month later.[6] Goodell initially suspended Rice for two games—but after additional footage later surfaced, Goodell unilaterally retracted the initial punishment and suspended Rice indefinitely.[7] Assuming Goodell believed the initial suspension to be insufficient, Rice and the National Football League Players Association (NFLPA) argued that Rice never lied or misled the NFL, and that Rice was basically punished twice for the same offense—state and federal governments are prohibited from prosecuting individuals for the same crime on more than one occasion under the Fifth Amendment’s Double Jeopardy Clause.[8] The NFL later admitted to never seeing the actual video before sentencing Rice.[9] Rice then appealed his suspension through arbitration.[10] Arbitrator and former U.S. District Judge Barbara S. Jones reversed Rice’s indefinite suspension because she believed Goodell acted in an arbitrary manner, and abused his discretionary power—freeing Rice to play again.[11] Moreover, Rice’s case never made it to trial. He was cleared of criminal charges after being accepted into a pretrial intervention program.[12] Ultimately, NFL Executive Vice President and General Counsel, Jeff Pash, acknowledged that it was a mistake in the past to rely solely on the criminal justice system when deciding initial discipline for violations of the personal conduct policy.[13]

On February 19, 2014, a videotape surfaced of Rice’s involvement in a violent domestic dispute with his then-fiancée in a hotel elevator.[5] Rice was indicted on aggravated assault charges a month later.[6] Goodell initially suspended Rice for two games—but after additional footage later surfaced, Goodell unilaterally retracted the initial punishment and suspended Rice indefinitely.[7] Assuming Goodell believed the initial suspension to be insufficient, Rice and the National Football League Players Association (NFLPA) argued that Rice never lied or misled the NFL, and that Rice was basically punished twice for the same offense—state and federal governments are prohibited from prosecuting individuals for the same crime on more than one occasion under the Fifth Amendment’s Double Jeopardy Clause.[8] The NFL later admitted to never seeing the actual video before sentencing Rice.[9] Rice then appealed his suspension through arbitration.[10] Arbitrator and former U.S. District Judge Barbara S. Jones reversed Rice’s indefinite suspension because she believed Goodell acted in an arbitrary manner, and abused his discretionary power—freeing Rice to play again.[11] Moreover, Rice’s case never made it to trial. He was cleared of criminal charges after being accepted into a pretrial intervention program.[12] Ultimately, NFL Executive Vice President and General Counsel, Jeff Pash, acknowledged that it was a mistake in the past to rely solely on the criminal justice system when deciding initial discipline for violations of the personal conduct policy.[13]

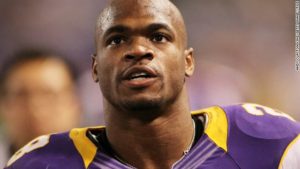

The NFL found itself facing yet another personal conduct issue in the summer of 2014 when Peterson was indicted by a Montgomery County, Texas grand jury on charges of reckless or negligent injury to a child.[14] After being placed on the Exempt/Commissioner Permission list during Week 3 (e.g. suspended with pay), Peterson pled no contest to misdemeanor reckless assault charges involving his four-year old son.[15] Peterson then sought a request for immediate reinstatement following his plea deal.[16] Goodell rejected Peterson’s request for reinstatement, and twelve days later, suspended Peterson for the rest of the 2014 season, without pay.[17] Goodell possessed the authority to determine whether the exemption should be lifted, which would have allowed Peterson to return to his Club’s Active List.[18] But Goodell maintained that Peterson had not shown remorse, and advised him to seek counseling.[19] As seen in the Rice appeal, Peterson and the NFLPA accused Goodell in U.S. District Court of retroactively penalizing players.[20] Judge David S. Doty vacated the arbitration ruling based on arbitrator bias, and believed Peterson was unfairly penalized.[21] Although this case may have been just another example of how the NFL was in dire need of revisions to their 2007 policy, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit later struck down Judge Doty’s decision in a victory for the NFL.[22]

The NFL found itself facing yet another personal conduct issue in the summer of 2014 when Peterson was indicted by a Montgomery County, Texas grand jury on charges of reckless or negligent injury to a child.[14] After being placed on the Exempt/Commissioner Permission list during Week 3 (e.g. suspended with pay), Peterson pled no contest to misdemeanor reckless assault charges involving his four-year old son.[15] Peterson then sought a request for immediate reinstatement following his plea deal.[16] Goodell rejected Peterson’s request for reinstatement, and twelve days later, suspended Peterson for the rest of the 2014 season, without pay.[17] Goodell possessed the authority to determine whether the exemption should be lifted, which would have allowed Peterson to return to his Club’s Active List.[18] But Goodell maintained that Peterson had not shown remorse, and advised him to seek counseling.[19] As seen in the Rice appeal, Peterson and the NFLPA accused Goodell in U.S. District Court of retroactively penalizing players.[20] Judge David S. Doty vacated the arbitration ruling based on arbitrator bias, and believed Peterson was unfairly penalized.[21] Although this case may have been just another example of how the NFL was in dire need of revisions to their 2007 policy, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit later struck down Judge Doty’s decision in a victory for the NFL.[22]

On August 4, 2016 a three-judge federal appeals court panel unanimously reversed Judge Doty’s earlier decision, as the panel ruled that “[Goodell] was within [his] rights when [he] suspended Minnesota Vikings star Adrian Peterson in 2014 after he was charged with child abuse.”[23] The ruling did not affect Peterson’s eligibility to play in the 2016 season, but does reaffirm the fine imposed by the League.[24] More importantly, this decision further strengthened Goodell’s ability to render punishment based on personal conduct violations. The panel concluded that the parties bargained to be bound by the decision of the arbitrator, and the arbitrator acted within his authority:

The Commissioner is the chief executive officer of the NFL . . . Article 46 of the [NFL Collective Bargaining] Agreement authorizes the Commissioner to impose discipline for “conduct detrimental to the integrity of, or public confidence in, the game of football.” The standard NFL player contract further acknowledges that the Commissioner has the power “to fine player in a reasonable amount; to suspend player for a period certain or indefinitely; and/or to terminate this contract.” The Agreement does not define “conduct detrimental” or prescribe maximum or presumptive punishments for such conduct.[25]

Ultimately, the NFL Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA) gave Goodell the power to alter punishment without seeking the approval of the players’ union, and that the punishment in the Peterson case was properly applied.[26]

Under the 2007 Personal Conduct Policy (2007 Policy), players accused of domestic violence were suspended on average about one and a half games, in contrast to the 2014 revisions to the policy that now makes punishments much harsher.[27] When compared to the 2014 Policy, prohibited conduct described under the 2007 Policy was much more limited in scope. Before 2014, prohibited conduct included: 1) any crime involving the threat of physical violence, 2) use of a deadly weapon in the commission of a crime, 3) possession or distribution of a weapon that violates state or federal law, 4) involvement in “hate crimes” or crimes of domestic violence, 5) theft, larceny or other property crimes, 6) sex offenses, and 7) racketeering, money laundering, obstruction of justice, resisting arrest, fraud, and violent or threatening conduct.[28] Any person who violated the 2007 Policy was required to undergo a consultation and counseling, and their failure to comply would be considered detrimental conduct punishable by fine or suspension at the discretion of the Commissioner.[29] If a player was convicted of or admitted to a criminal violation, including a plea to a lesser included offense or no contest, then they would be subject to discipline that included a fine, suspension without pay, and/or banishment from the League.[30] The Commissioner not only determined initial punishment, but a second criminal violation allowed the Commissioner to suspend a player without pay or even banish them for a period of time at his discretion.[31] The 2007 Policy also attempted to deter players who threatened or committed violent acts against coworkers in the workplace by allowing for the possibility of employment termination.[32] Under the 2007 Policy, Club and League entities had a duty to report prohibited conduct to Club and NFL Security to ensure the effective administration of the 2007 Policy.[33] Each player that was suspended under the 2007 Policy had to apply for reinstatement after their suspension ended.[34] Furthermore, any player who was disciplined under the 2007 Policy had a right to appeal, which included a hearing before the Commissioner or his designee.[35] Due to its facially ambiguous nature, the 2007 Policy seemed more concerned with regulating the personal lives of players than addressing foreseeable conduct that would eventually spawn into a public relations nightmare.

The first two athletes to feel the bite of the 2007 Policy were Adam “Pacman” Jones (Jones), who at the time played for the Tennessee Titans, and the late Chris Henry (Henry) of the Cincinnati Bengals. After becoming Commissioner in 2006, Goodell was poised to create a policy that would allow the League to impose harsher and quicker discipline to players who encounter off-the-field problems.[36] Jones was involved in a shooting that left a victim with a severed spinal cord; he was subsequently suspended for the entire 2007 NFL season.[37] Henry, who died in a tragic car accident in 2009, was suspended for the first eight games of the 2007 NFL season after being accused of aggravated assault with a firearm, providing female minors with alcohol, driving while drunk, and assault.[38] Although the 2007 policy addressed certain types of player misconduct, it was still ineffective in deterring conduct the NFL deemed to be detrimental to the League.

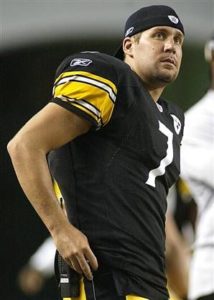

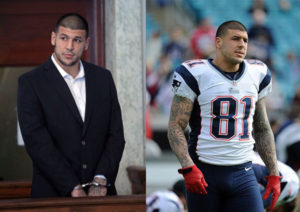

Four years before the Rice incident, Pittsburgh Steeler quarterback Ben Roethlisberger (Roethlisberger) was the first player in League history to be suspended under the Personal Conduct Policy without being charged with a crime.[39] Roethlisberger was accused of sexual assault in June 2008, and although no charges were filed in the case, he was again accused of sexual assault in March of 2010.[40] Goodell suspended Roethlisberger for six games, but the suspension was later reduced to four games.[41] Goodell believed that Roethlisberger’s conduct raised sufficient concerns that Goodell believed warranted effective intervention for Roethlisberger’s personal and professional welfare.[42] As Goodell had struggled with off-the-field player misconduct since the beginning of his tenure as Commissioner, the Aaron Hernandez (Hernandez) murder case added to the list of high-profile issues Goodell and the NFL were forced to address—somewhat setting the stage for the implementation of a new personal conduct policy after the Rice and Peterson incidents.

Four years before the Rice incident, Pittsburgh Steeler quarterback Ben Roethlisberger (Roethlisberger) was the first player in League history to be suspended under the Personal Conduct Policy without being charged with a crime.[39] Roethlisberger was accused of sexual assault in June 2008, and although no charges were filed in the case, he was again accused of sexual assault in March of 2010.[40] Goodell suspended Roethlisberger for six games, but the suspension was later reduced to four games.[41] Goodell believed that Roethlisberger’s conduct raised sufficient concerns that Goodell believed warranted effective intervention for Roethlisberger’s personal and professional welfare.[42] As Goodell had struggled with off-the-field player misconduct since the beginning of his tenure as Commissioner, the Aaron Hernandez (Hernandez) murder case added to the list of high-profile issues Goodell and the NFL were forced to address—somewhat setting the stage for the implementation of a new personal conduct policy after the Rice and Peterson incidents.

In June of 2013, Massachusetts State Police began investigating Hernandez, a former Pro-Bowl tight-end for the New England Patriots, in connection with the shooting death of Hernandez’s friend Odin Lloyd (Lloyd).[43] Lloyd’s body was found in an industrial park just a mile and a half away from Hernandez’s home. After obtaining a search warrant, Hernandez was accused of intentionally destroying his home security system and later turned over his demolished phone to authorities. Robert Kraft (Kraft), owner of the New England Patriots, decided days before Hernandez’s trial that if Hernandez was charged with a crime related to the murder of Lloyd, even obstruction of justice, he would be released from the team.[44] Hernandez was later released from the Patriots after being charged and convicted of first-degree murder and five other weapon charges stemming from the case.[45] In April of 2015, Hernandez was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.[46]

In June of 2013, Massachusetts State Police began investigating Hernandez, a former Pro-Bowl tight-end for the New England Patriots, in connection with the shooting death of Hernandez’s friend Odin Lloyd (Lloyd).[43] Lloyd’s body was found in an industrial park just a mile and a half away from Hernandez’s home. After obtaining a search warrant, Hernandez was accused of intentionally destroying his home security system and later turned over his demolished phone to authorities. Robert Kraft (Kraft), owner of the New England Patriots, decided days before Hernandez’s trial that if Hernandez was charged with a crime related to the murder of Lloyd, even obstruction of justice, he would be released from the team.[44] Hernandez was later released from the Patriots after being charged and convicted of first-degree murder and five other weapon charges stemming from the case.[45] In April of 2015, Hernandez was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.[46]

It was clear that Goodell needed to implement a policy that would not only educate players on the type of detrimental conduct that would not be tolerated, but Goodell also needed a policy that demonstrated to the public that he was well equipped in dealing with player misconduct quickly and effectively. Thus, Goodell implemented stricter punishments for player violations under the new personal conduct policy, and provided players with more education and training on domestic violence. Probably one of the most evident changes to the policy is the new six game suspensions for first-time offenders, which is a monumental difference from before, where players in the past were suspended on average one and a half games for prior domestic violence incidents before 2014.[47] Furthermore, a player’s second offense can bring with it a “lifetime ban” from the NFL.[48]

The 2014 Policy also has unilaterally added causal violations stemming from violence against others.[49] Whether a player’s conduct involves actual or threatened violence against another person, or their conduct poses a “genuine” danger to the safety or well-being of others, players are now held to an even higher standard than before.[50] Counseling and treatment services are now provided to not only domestic violence victims and the families of victims, but Goodell has also started an NFL program that educates high school students on domestic violence.[51] Yet many across the League, players and critics alike, believed that Goodell did not have the authority to unilaterally implement such dramatic changes to the collectively bargained Personal Conduct Policy.[52]

The 2014 Policy also has unilaterally added causal violations stemming from violence against others.[49] Whether a player’s conduct involves actual or threatened violence against another person, or their conduct poses a “genuine” danger to the safety or well-being of others, players are now held to an even higher standard than before.[50] Counseling and treatment services are now provided to not only domestic violence victims and the families of victims, but Goodell has also started an NFL program that educates high school students on domestic violence.[51] Yet many across the League, players and critics alike, believed that Goodell did not have the authority to unilaterally implement such dramatic changes to the collectively bargained Personal Conduct Policy.[52]

Goodell was not only being accused of wielding too much power in assessing penalties for violations of the Policy, but his leadership was now in question as well.[53] Goodell exercised his delegated authority under the NFL Constitution and Bylaws to unilaterally implement revisions regarding the type of conduct and initial discipline that players will be subject to for violating the 2014 Policy. With many calling for an independent arbitrator, Goodell apologized for the “mishandling [of] cases involving domestic violence and admitted . . . [he] did not understand the severity and scope of the accusations.”[54] Players, and even members of women support groups, such as UltraViolet, thought the NFL lacked effective leadership.[55] Contrary to what players believed, owners agreed with Goodell, and stood in solidarity.[56] Goodell had the overwhelming support of many owners across the League, as they believed the revisions were necessary in dealing with conduct that was detrimental to the integrity of the NFL.[57] Goodell’s revisions were aimed at holding all NFL personnel to a higher standard of conduct in a way that is responsible—attempting to unilaterally act in order to further promote the values of the NFL.

The NFLPA, who is the authorized player-representative that negotiates mandatory subjects of collective bargaining on behalf of players, was extremely dissatisfied that they were not able to collectively bargain changes to the 2007 Policy.[58] Goodell sent a memo to owners just prior to making a press release regarding changes to the Policy, and attached a copy of the NFL’s mission statement, which outlined that being part of the NFL is a privilege, not a right.[59] Goodell was certain that the measures adopted would uphold that principle, as Goodell stated in the memo to owners that he would “no longer defer entirely to the decisions of the criminal justice system, which is governed by the processes and considerations that are not appropriate to workplace, especially a workplace as visible and influential as [the NFL].”[60] Despite the fact that Goodell wants the NFL to continuously review and refresh its standards and policies, the unilateral change made to a mandatory subject of the CBA can arguably be seen as an unfair labor practice under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA). The NFLPA believed that they were not offered the professional courtesy of seeing the NFL’s new personal conduct policy before it hit the presses, and believed that Goodell’s unilateral decision and conduct is the only thing that has been consistent over the past few months.[61] Thus, the NFLPA, current and former players, and former NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue felt the need to share their opinions on the unfettered discretion Goodell was exercising.

As the NFLPA decided to file a grievance due to Goodell’s violation of the CBA and his authority to make wide-ranging decisions on discipline, players continued to argue that the new policy is a change in the terms and conditions of employment: the NLRA states that such changes in unionized situations are subject to collective bargaining.[62] Richard Sherman (Sherman), the outspoken cornerback for the Seattle Seahawks and team player representative, found it interesting that the changes made to the CBA were not collectively bargained for, and felt as if the NFL were making these changes by the seat of its pants and making it up as they go along.[63] Sherman explicitly stated that players should have had more input on the new policy, and in response to Sherman’s public statements, Goodell sent a letter to fans stating that “[o]ur communities are the heart of our teams and we put everything into making a positive impact on them . . . Character and values sits above everything else because we represent something that means so much to so many people.”[64] Yet, many around the League feel as if the key ingredient missing from the relationship between the union and the players is trust.

Former NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue went on record to say that the players feel the NFL and Goodell do not truly care about them as human beings and equal partners.[65] In April of 2016, New Orleans Saints quarterback Drew Brees (Brees) stated that he believed Goodell possessed too much power.[66] As Goodell plays judge, jury, and executioner when it comes to discipline, Brees believed that Goodell could not be trusted in any League-led investigation, or when it comes to anything for that matter, and put simply: Goodell is not transparent.[67] On April 11, 2016, an arbitrator upheld Goodell’s unilateral implementation on his wide-ranging decisions on discipline, as well as Goodell’s use of paid leave and the use of the Commissioner Exempt List in disciplining players accused of being in violation of the 2014 Policy.[68] The question that many have is what inspired Goodell to include such a thorough list of prohibited conduct, and how was he going to effectively deal with enforcement?

Former NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue went on record to say that the players feel the NFL and Goodell do not truly care about them as human beings and equal partners.[65] In April of 2016, New Orleans Saints quarterback Drew Brees (Brees) stated that he believed Goodell possessed too much power.[66] As Goodell plays judge, jury, and executioner when it comes to discipline, Brees believed that Goodell could not be trusted in any League-led investigation, or when it comes to anything for that matter, and put simply: Goodell is not transparent.[67] On April 11, 2016, an arbitrator upheld Goodell’s unilateral implementation on his wide-ranging decisions on discipline, as well as Goodell’s use of paid leave and the use of the Commissioner Exempt List in disciplining players accused of being in violation of the 2014 Policy.[68] The question that many have is what inspired Goodell to include such a thorough list of prohibited conduct, and how was he going to effectively deal with enforcement?

Although Goodell had promised to overhaul the Personal Conduct Policy by the end of the 2014 season, his revisions are said to reflect similarities to the rules established by the New York Police Department when handling similar cases.[69] Goodell most noticeably added a more extensive list of prohibited conduct, with an increased baseline suspension for first-time offenders:

Violations involving assault, battery, domestic violence, or sexual assault will result in a baseline six-game suspension without pay, with more if aggravating factors are present, such as the use of a weapon or a crime against a child. A second offense will result in banishment from the NFL.[70]

Additionally, Goodell has added stalking, harassment, crimes of dishonesty (e.g. blackmail, extortion, and fraud), crimes against law enforcement, and disorderly conduct to the list of prohibited conduct.[71] Anyone arrested or charged with violent or threatening conduct that would violate the 2014 Policy will be offered a formal clinical evaluation, and any information obtained during the evaluation may be taken into consideration when determining initial discipline. Goodell also appointed a Special Counsel for Investigations and Conduct who will undertake investigations, oversee investigatory procedures, and issue initial discipline for violations of the 2014 Policy.[72] Any player who directly or indirectly through others interferes in any matter with an investigation will face separate disciplinary action under the 2014 policy.[73] Ultimately, this revision allows for the Commissioner to rely on a qualified individual with a criminal justice background to make decisions concerning initial discipline, while still preserving the Commissioner’s authority to rule on appeals.[74]

The 2014 Policy also includes a Conduct Committee comprised of nine NFL owners, two of which are former players, who will annually review the 2014 Policy and recommend changes moving forward.[75] Members of the Committee include: Arizona Cardinals owner Michael Bidwill as the chairman; Atlanta Falcons owner Arthur Blank; Kansas City Chiefs owner Clark Hunt; Dee Haslam, the wife of Cleveland Browns owner Jimmy Haslam; Dallas Cowboys Executive Vice President Charlotte Jones Anderson, chairwoman of the NFL Foundation; Chicago Bears owner George McCaskey; Houston Texans owner Robert McNair; and two former NFL players with stake in ownership, Warren Dunn of the Falcons and John Stallworth of the Pittsburgh Steelers.[76] With the help of subject matter experts, the Committee will make annual recommendations on investigatory practices, disciplinary levels or procedures, and service components of the 2014 Policy.[77] Lastly, to assure the 2014 Policy exhibits best practices in academia, business, and public sector settings—the Committee may seek the advice from current and former players, as well as a broad and diverse group of outside experts.[78]

The 2014 Policy also includes a Conduct Committee comprised of nine NFL owners, two of which are former players, who will annually review the 2014 Policy and recommend changes moving forward.[75] Members of the Committee include: Arizona Cardinals owner Michael Bidwill as the chairman; Atlanta Falcons owner Arthur Blank; Kansas City Chiefs owner Clark Hunt; Dee Haslam, the wife of Cleveland Browns owner Jimmy Haslam; Dallas Cowboys Executive Vice President Charlotte Jones Anderson, chairwoman of the NFL Foundation; Chicago Bears owner George McCaskey; Houston Texans owner Robert McNair; and two former NFL players with stake in ownership, Warren Dunn of the Falcons and John Stallworth of the Pittsburgh Steelers.[76] With the help of subject matter experts, the Committee will make annual recommendations on investigatory practices, disciplinary levels or procedures, and service components of the 2014 Policy.[77] Lastly, to assure the 2014 Policy exhibits best practices in academia, business, and public sector settings—the Committee may seek the advice from current and former players, as well as a broad and diverse group of outside experts.[78]

In appropriate cases involving domestic violence, child abuse, or sexual assault, the NFL has also implemented specialized club-level Critical Response Teams.[79] These teams shall provide assistance and resources to victims and families, as well as the employee involved in a reported incident.[80] Teams are responsible in developing protocols based on experts’ recommendations of appropriate and constructive responses to the types of reported incidents mentioned above. Assistance by these Critical Response Teams may include providing or direction to appropriate counseling, social and other services, clergy, medical professionals, and specialists in dealing with children and youth.[81] As domestic violence and similar incidents involving family violence have become an increasing concern throughout professional sports, it seems the NFL’s implementation of Critical Response Teams is geared toward educating and providing immediate support to all parties affected by this type of detrimental personal conduct.

Most recently, the NFL has had to deal with the personal conduct violations of defensive end Greg Hardy (Hardy), quarterback Johnny Manziel (Manziel), and running back LeSean McCoy (McCoy). Hardy was suspended ten games without pay after a two-month investigation found sufficient credible evidence that Hardy “engaged in conduct that violated NFL policies in multiple respects and [had] aggravated consequences.”[82] Hardy had multiple domestic-violence charges leading up to his ten-game suspension. Lisa Friel, who was formerly the head of the Sex Crimes Prosecution Unit in the New York County District Attorney’s Office and is now NFL Senior Vice President and counsel for investigations, found that “[Hardy] used physical force against [his former girlfriend] which caused her to land in both a bathtub” and “on a futon covered with at least four semi-automatic rifles.”[83] Reports also illustrated that Hardy assaulted his former girlfriend by pushing and putting his hands around her neck.[84] The toughened 2014 Policy governing off-field behavior considered Hardy’s use of physical force a significant act of violence in violation of the 2014 Policy. Ultimately, Hardy lost nearly $5.8 million of his $9 million in per-game bonuses, and was also warned by Goodell that any further adverse involvement with law enforcement or violations of the 2014 Policy would result in Hardy being banished from the League forever.[85]

Most recently, the NFL has had to deal with the personal conduct violations of defensive end Greg Hardy (Hardy), quarterback Johnny Manziel (Manziel), and running back LeSean McCoy (McCoy). Hardy was suspended ten games without pay after a two-month investigation found sufficient credible evidence that Hardy “engaged in conduct that violated NFL policies in multiple respects and [had] aggravated consequences.”[82] Hardy had multiple domestic-violence charges leading up to his ten-game suspension. Lisa Friel, who was formerly the head of the Sex Crimes Prosecution Unit in the New York County District Attorney’s Office and is now NFL Senior Vice President and counsel for investigations, found that “[Hardy] used physical force against [his former girlfriend] which caused her to land in both a bathtub” and “on a futon covered with at least four semi-automatic rifles.”[83] Reports also illustrated that Hardy assaulted his former girlfriend by pushing and putting his hands around her neck.[84] The toughened 2014 Policy governing off-field behavior considered Hardy’s use of physical force a significant act of violence in violation of the 2014 Policy. Ultimately, Hardy lost nearly $5.8 million of his $9 million in per-game bonuses, and was also warned by Goodell that any further adverse involvement with law enforcement or violations of the 2014 Policy would result in Hardy being banished from the League forever.[85]

Manziel, familiarly known as “Johnny Football,” has been in the news considerably after his alleged physical altercation with his former girlfriend, which inevitably resulted in the Cleveland Browns releasing Manziel after the completion of the 2016 season.[86] The issue presented before Goodell was whether Manziel’s incident with his former girlfriend involved physical violence or the threat of physical violence, and whether Manziel’s driving posed a genuine danger to others.[87] Manziel was stopped by police in Avon, Ohio on October 12, 2015 after witnesses saw Manziel and ex-girlfriend arguing in a vehicle that was traveling at a high rate of speed, which then escalated to the point that Manziel’s girlfriend tried to leave the car as it exited a highway.[88] Manziel was later accused of striking his ex-girlfriend so hard in the ear that she was unable to hear out of one ear for several days.[89] On April 27, 2016, a Texas grand jury indicted the free-agent on a misdemeanor assault charge.[90] Under the 2014 Policy, Goodell’s discipline for Manziel could be a fine or suspension, as many predict that he will serve a heavy suspension before ever playing with another NFL team. Moreover, the NFL announced on June 30, 2016 that Manziel would be suspended four games for violation of the NFL’s substance abuse policy, which is unrelated to his current unresolved assault case.[91]

Manziel, familiarly known as “Johnny Football,” has been in the news considerably after his alleged physical altercation with his former girlfriend, which inevitably resulted in the Cleveland Browns releasing Manziel after the completion of the 2016 season.[86] The issue presented before Goodell was whether Manziel’s incident with his former girlfriend involved physical violence or the threat of physical violence, and whether Manziel’s driving posed a genuine danger to others.[87] Manziel was stopped by police in Avon, Ohio on October 12, 2015 after witnesses saw Manziel and ex-girlfriend arguing in a vehicle that was traveling at a high rate of speed, which then escalated to the point that Manziel’s girlfriend tried to leave the car as it exited a highway.[88] Manziel was later accused of striking his ex-girlfriend so hard in the ear that she was unable to hear out of one ear for several days.[89] On April 27, 2016, a Texas grand jury indicted the free-agent on a misdemeanor assault charge.[90] Under the 2014 Policy, Goodell’s discipline for Manziel could be a fine or suspension, as many predict that he will serve a heavy suspension before ever playing with another NFL team. Moreover, the NFL announced on June 30, 2016 that Manziel would be suspended four games for violation of the NFL’s substance abuse policy, which is unrelated to his current unresolved assault case.[91]

Another player who was in the news for personal conduct issues during the close of the 2015 season was Buffalo Bills running back McCoy. McCoy and another teammate were involved in a fight with a couple of off-duty police officers over a bottle of champagne in a Philadelphia night club in February 2016.[92] Charges were not filed against McCoy, as the Philadelphia District Attorney’s office believed that there was not enough evidence presented in order to charge McCoy of assault and battery.[93] Although his personal conduct off the field has been stellar to this point, McCoy could have found himself suspended by Goodell due to his conduct being detrimental to the League. Ultimately, McCoy was not suspended or fined for his role in the nightclub brawl.[94]

Another player who was in the news for personal conduct issues during the close of the 2015 season was Buffalo Bills running back McCoy. McCoy and another teammate were involved in a fight with a couple of off-duty police officers over a bottle of champagne in a Philadelphia night club in February 2016.[92] Charges were not filed against McCoy, as the Philadelphia District Attorney’s office believed that there was not enough evidence presented in order to charge McCoy of assault and battery.[93] Although his personal conduct off the field has been stellar to this point, McCoy could have found himself suspended by Goodell due to his conduct being detrimental to the League. Ultimately, McCoy was not suspended or fined for his role in the nightclub brawl.[94]

The CBA may provide Goodell with the delegated authority to unilaterally make changes to the 2014 Policy, but with a background made up of almost entirely public relations work before stepping into power as Commissioner, those familiar with the NFL believe Goodell should not be overseeing discipline policies. Players are frustrated with the lack of consistency regarding imposed suspensions by Goodell, as there is much more leeway for Goodell to treat more harshly players who subjectively tarnish the NFL shield.[95] Many believe the 2014 Policy is not about imposing effective discipline—it is about public relations and damage control.[96] Proscribing for optional counseling and evaluation for current and prospective players does nothing to affect better conduct. Goodell is seemingly establishing a status quo, creating precedent, and allowing for other professional sports leagues to unilaterally impose discipline.[97] Some veteran players even believed they could have taken on the role of authoritarian in helping the younger guys avoid behavioral misconduct, instead, Goodell chose to go public with a new policy before informing all current players.[98] For this reason, it’s hard to fault players in assuming that Goodell and the NFL does not view nearly all 1700 players as legitimate business partners.

The 2014 Policy presumptuously indicates the lack of diverse voices during the bargaining process, and some believe it possibly illuminates a larger problem: Goodell’s fascination with maximizing top-line revenue by providing a false sense of transparency. One legal analyst agreed that the new policy is about the NFL saving face, keeping players on the field, profits in their pockets and the power in Goodell’s hands.[99] In comparison to the 2007 Policy, the 2014 Policy has similar characteristics: ambiguous, optional, case-by-case, complicated, and at the discretion of Goodell.[100] There are still many glaring holes in the 2014 policy. One hole in the 2014 policy concerns players that violate the Personal Conduct Policy—will counseling be mandatory, or just provided? Unfortunately, many believe Goodell and the NFL are not qualified to handle domestic violence trainings, as only twenty percent of employers surveyed have training on domestic violence issues.[101] Thus, how can skeptics fully entrust in Goodell and the NFL that counseling and training will deter player misconduct involving domestic and family violence?

There may seem to be no clarity in the new policy; it mainly discusses what Goodell “may” do when a violation occurs.[102] Punishment under the new policy is vague, and could be strengthened by explicitly stating that any player arrested would immediately trigger suspension, while teams should possess the discretion to punish a player further. Goodell not only altered the forms of discipline outlined in the CBA, but some argue that he committed a blatant labor law violation.[103] Furthermore, Goodell’s unilateral actions may be viewed as purely a public relations maneuver aimed at publicly punishing players, and doing very little to prevent domestic violence. Players who have had historically clean track-records are now forced to attend mandatory domestic violence seminars before each season, as players believe they are being treated as perpetrators.[104] Also, the 2014 Policy forces players to “incriminate themselves and then an ambiguous standard of proof is applied to determine whether a violation has occurred.”[105] Overall, the 2014 Policy encapsulates Goodell’s “best interest” power as Commissioner of the NFL and unilaterally enforces a type of “open and notorious” discipline upon players, having astounding effects on the number of violations leading up to the 2016 season.

Surprisingly, since the 2014 revisions of the Personal Conduct Policy, only thirty-five NFL players have “run afoul of the law in 2015 . . . and just two since the [beginning of the] 2015 season.”[106] Comparatively speaking, these recent numbers make up almost half of the seventy-one players from 2006, and below the 2000 and 2004 lows of thirty-nine.[107] There has been significant progress made by the NFL in relation to violations of the Personal Conduct Policy. NFL spokesman Brian McCarthy mentioned that the recent statistics are “[a] positive reflection on the players and the [NFL’s] educational, preventative, and deterrence programs.”[108] Furthermore, the NFL has sent a strong message to not only players, but to all NFL personnel that conduct detrimental to the integrity of and public confidence in the NFL will lead to swift and effective discipline.

With the recent changes and revisions to the policy, Goodell still possesses significant powers when it comes to initial investigations and appeals. If any NFL player or personnel is formally charged with a crime of violence, or if an investigation leads the Commissioner to believe that one has violated the 2014 Policy, the Commissioner has the delegated authority to act where circumstances warrant doing so.[109] If a violation relating to a crime of violence is suspected, but further investigation is required, the Commissioner may determine to place a player or employee on leave with pay on a limited and temporary basis to permit the League to conduct an investigation.[110] A player who is placed on the Commissioner Exempt List may not practice or attend games, and non-player employees placed on administrative leave may be present only on such basis as is approved by Goodell.[111] But probably one of the most important aspects of the 2014 Policy that has reluctantly not changed is Goodell retaining the authority to rule on appeals.

During the appeal process, an NFL Expert Review Panel consisting of three outside experts will make recommendations to the Commissioner or his designee on an appeal ruling; the Commissioners has final authority.[112] Kraft believed Goodell should have appeals oversight because he “understands the best interest of the game.”[113] After Goodell or his designee reviews the panel’s recommendation during the appeal, Goodell or his designee has the authority to make a final decision on disciplinary measures.[114] Goodell and the NFL have a glaring advantage throughout this process—cleverly choosing not to collectively bargain the pool of potential “designee(s)” that shall be assigned by the Commissioner. Conversely, the use of a “designee” may increase the likelihood the NFL could possibly find itself adversely impacted by future arbitration decisions concerning the issue of retroactive punishment or an abuse of discretionary power during the appeal process. The Tom Brady (Brady) “Deflategate” scandal is a recent example of Goodell flexing his discretionary power during the appeal process.

In June of 2015, Goodell upheld the four-game suspension of the New England Patriots star quarterback Brady for his role in the use of improperly deflated footballs during the Patriots playoff game against the Indianapolis Colts.[115] Before appealing the suspension handed down by Goodell, the NFLPA urged that Goodell recuse himself from the appeal, but Goodell refused and the suspension was upheld.[116] In September of that same year, Brady’s suspension was overturned by a Federal Court judge, who believed Goodell administered his “own brand of industrial justice.”[117] After Brady played the entire 2015 season, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit handed down a ruling on April 25, 2016 that reaffirmed Goodell’s broad authority to administer discipline as he pleases, and affirmed his power under the CBA.[118]

Brady later filed a second appeal in the Second Circuit on May 23, 2016, but was denied nearly two months later.[119] The Second Circuit implicitly reaffirmed the Court of Appeals ruling that the parties contracted under the CBA to specifically allow the Commissioner to sit as arbitrator, and the court may not disturb an award so long as the arbitrator acted within the bounds of his bargained-for authority.[120] Thus, Brady’s four-game suspension for the 2016 season was upheld, and will not be brought forth on appeal to the Supreme Court.[121] Brady’s lawsuit and appeal was less about the under-inflation of footballs, and more about whether Goodell has the power to deliver a harsh penalty for “conduct detrimental” to the NFL under the League’s CBA.[122] It was obvious Goodell may have dropped the ball in the Rice case due to the added punishment he rendered once additional footage leaked out to the public. But the Brady case is much different; Brady’s suspension was the product of a thorough investigation, and a lengthy hearing over which Goodell presided.[123] Therefore, the recent Brady decision symbolizes Goodell’s strengths and his bargained-for authority to discipline players under the CBA.

Brady later filed a second appeal in the Second Circuit on May 23, 2016, but was denied nearly two months later.[119] The Second Circuit implicitly reaffirmed the Court of Appeals ruling that the parties contracted under the CBA to specifically allow the Commissioner to sit as arbitrator, and the court may not disturb an award so long as the arbitrator acted within the bounds of his bargained-for authority.[120] Thus, Brady’s four-game suspension for the 2016 season was upheld, and will not be brought forth on appeal to the Supreme Court.[121] Brady’s lawsuit and appeal was less about the under-inflation of footballs, and more about whether Goodell has the power to deliver a harsh penalty for “conduct detrimental” to the NFL under the League’s CBA.[122] It was obvious Goodell may have dropped the ball in the Rice case due to the added punishment he rendered once additional footage leaked out to the public. But the Brady case is much different; Brady’s suspension was the product of a thorough investigation, and a lengthy hearing over which Goodell presided.[123] Therefore, the recent Brady decision symbolizes Goodell’s strengths and his bargained-for authority to discipline players under the CBA.

Goodell flexed his authoritative power once again in June of 2016 after a December 2015 Al Jazeera America report alleged performance-enhancing drug use by several high-profile players.[124] Under the current CBA, the NFL and NFLPA are obligated and have a shared responsibility to look into any allegations that could impact the integrity of competition on the field and the health of NFL players.[125] The Al Jazeera America report raised serious issues implicating five players and their possible violation of the NFL’s policy on Performance-Enhancing Substances.[126] With no substantive evidence other than allegations by a former anti-aging clinic intern—who later recanted his statements—the NFL chose to investigate five players who were mentioned in the report: former Denver Broncos’ quarterback Peyton Manning (Manning), Pittsburgh Steelers’ James Harrison (Harrison), Green Bay Packers’ Julius Peppers (Peppers) and Clay Matthews (Matthews), and now free-agent Mike Neal.[127] The NFLPA believed the League’s investigation of players set a precedent, allowing the NFL to interview anyone about anything without regard for evidence or the source of the allegations.[128] After players were accused publicly, they were given ten days to agree to interviews by August 25, 2016 or be suspended indefinitely by Goodell for conduct detrimental to the League.[129] Although Manning was subsequently cleared after cooperating with League investigators, Goodell had every right under Article 46 of the CBA to suspend players who did not cooperate with the Al Jazeera investigation and comply with being interviewed by League investigators.

Goodell flexed his authoritative power once again in June of 2016 after a December 2015 Al Jazeera America report alleged performance-enhancing drug use by several high-profile players.[124] Under the current CBA, the NFL and NFLPA are obligated and have a shared responsibility to look into any allegations that could impact the integrity of competition on the field and the health of NFL players.[125] The Al Jazeera America report raised serious issues implicating five players and their possible violation of the NFL’s policy on Performance-Enhancing Substances.[126] With no substantive evidence other than allegations by a former anti-aging clinic intern—who later recanted his statements—the NFL chose to investigate five players who were mentioned in the report: former Denver Broncos’ quarterback Peyton Manning (Manning), Pittsburgh Steelers’ James Harrison (Harrison), Green Bay Packers’ Julius Peppers (Peppers) and Clay Matthews (Matthews), and now free-agent Mike Neal.[127] The NFLPA believed the League’s investigation of players set a precedent, allowing the NFL to interview anyone about anything without regard for evidence or the source of the allegations.[128] After players were accused publicly, they were given ten days to agree to interviews by August 25, 2016 or be suspended indefinitely by Goodell for conduct detrimental to the League.[129] Although Manning was subsequently cleared after cooperating with League investigators, Goodell had every right under Article 46 of the CBA to suspend players who did not cooperate with the Al Jazeera investigation and comply with being interviewed by League investigators.

Green Bay Packers’ Matthews, who was later cleared along with teammate Peppers and Steelers linebacker Harrison, believed that being forced to provide testimony to League investigators sets a dangerous precedent, but he believes players chose to cooperate in fear of being martyrs to the cause at the cost of being suspended from their teams.[130] Matthews does not seem to be the only individual who may have a problem with Goodell’s unfettered power over disciplinary matters. Recently, the New York Times stated that Goodell’s application of the NFL’s disciplinary policy, “and his unwillingness to appoint an independent arbitrator to hear appeals, has corroded the fragile trust between him and the players, who see him as judge and jury.”[131] With the NFL’s current labor deal expiring in 2021, players have begun to focus on limiting Goodell’s power when it comes to the appeal process, which they believe Goodell has utilized to penalize players for transgressions that seem like nothing more than ambiguous infractions.[132] Players are not only seeking the implementation of a neutral arbitrator to hear all player discipline appeals, but as many believe this to be the social-media age that allows for an avalanche of criticisms, players are hoping to ease the labor-management tension that has long been a feature of the NFL.[133] Ultimately, players feel the only viable option to challenge Goodell’s authority in applying the personal conduct policy is by choosing to fight their battle in the courts, yet owners have stood in agreeance that Goodell is best suited to protect the overall integrity of the game.[134]

The whole reason you have a commissioner in any sport, the most fundamental reason for that office, is to protect the integrity of the game,” said Jeff Pash, the N.F.L’s top lawyer. The job of the commissioner, he added, is to make sure that fans “are rooting and supporting financially and emotionally for a game that is clean, that is honest, cares about fans and cares about the people who play the game.[135]

Goodell and club owners were aware that the League’s 2007 Personal Conduct Policy was heavily flawed, and unfortunately these flaws were exacerbated by the untimely conduct of Rice and Peterson. Goodell was forced to take unprecedented steps in protecting the integrity and promoting the values of the NFL. He unilaterally implemented revisions that have added an extensive list of prohibited conduct, an increase baseline six-game suspension without pay, a Special Counsel for Investigations and Conduct, and specialized Critical Response Teams. Being highly criticized for his arbitrary use of power and decision-making, Goodell responded by assigning a special counsel with a criminal justice background to oversee initial investigations and to decide discipline for violations of the policy. The byproduct of such a comprehensive policy has led to the lowest amount of player violations beyond speeding tickets since the turn of the century. Unfortunately, NFL players have strongly criticized the Policy as not being truly effective in preventing domestic violence, and have argued that it fails to build trust among Goodell and the players.[136] Results speak volumes, but Goodell’s unilateral revisions to the NFL’s Personal Conduct Policy may be understood as a public relations move to reassure the public of the NFL’s effort to hold their employees to a higher standard of personal conduct.

Aaron Davis is a third-year law student at Marquette University Law School, and receives his Juris Doctor in May of 2017. Davis is a 2017 Sports Law Certificate recipient at Marquette through the National Sports Law Institute. During his law school tenure, Davis has garnered various types of experience, including working for the Wisconsin Court of Appeals Public Defender’s Office, and most recently, working as a legal intern for the Ladies Professional Golf Association. Davis is currently a staff member of the Marquette Sports Law Review, and legal intern at GameBreakers, LLC. Prior to Marquette, Davis was a Scholar Athlete at San Francisco State University, where he also earned his Bachelor of Arts in Criminal Justice Studies.

[1] NFL Approves “Tough” Personal Conduct Policy, CBS News (Dec. 10, 2014), http://www.cbsnews.com/news/nfl-unveils-tougher-personal-conduct-policy/.

[2] Id.

[3] Player Arrests Down in the NFL as Rice Still Lives ‘Nightmare’, AFP (Dec. 8. 2015), http://news.yahoo.com/player-arrests-down-nfl-rice-still-lives-nightmare-185952793–nfl.html;_ylt=A0LEVow7YXdWwkcAzrNx.9w4;_ylu=X3oDMTE0cjY0a25.

[4] NFL Approves “Tough” Personal Conduct Policy, supra note 1.

[5] Louis Bien, A Complete Timeline of the Ray Rice Assault Case, SBNation (Nov. 28, 2014), http://www.sbnation.com/nfl/2014/5/23/5744964/ray-rice-arrest-assault-statement-apology-ravens.

[6] Id.

[7] NFL Approves “Tough” Personal Conduct Policy, supra note 1.

[8] Id.

[9] Bien, supra note 5.

[10] Id.

[11] NFL Approves “Tough” Personal Conduct Policy, supra note 1.

[12] Bien, supra note 5.

[13] Id.

[14] Steve DiMatteo, A Timeline of the Adrian Peterson Child Abuse Case, SB Nation (Sep. 17, 2014), http://www.sbnation.com/2014/9/17/6334793/adrian-peterson-child-abuse-statement-vikings-timeline.

[15] Id.

[16] Adrian Peterson Timeline, NFL.com (Apr. 16, 2016), http://www.nfl.com/news/story/0ap3000000485782/article/adrian-peterson-timeline.

[17] Id.

[18] Kevin Patra, What is the Exempt List?, NFL.com (Sept. 17, 2014), http://www.nfl.com/news/story/0ap3000000396169/article/what-is-the-exempt-list.

[19] Ken Belson, Judge Overturns Suspension of Adrian Peterson, NY Times (Feb. 26, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/27/sports/football/adrian-petersons-suspension-is-overturned.html?_r=0.

[20]Id.

[21] Id.

[22] Appeals Court Rules in Favor of NFL in Adrian Peterson Case, NFL.com (Aug. 4, 2016), http://www.nfl.com/news/story/0ap3000000679721/article/appeals-court-rules-in-favor-of-nfl-in-adrian-peterson-case.

[23] Id.

[24] Matt Bonesteel, Federal Appeals Court Sides with NFL in Adrian Peterson Case, Washington Post (Aug. 4, 2016), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/early-lead/wp/2016/08/04/federal-appeals-court-sides-with-nfl-in-adrian-peterson-case/.

[25] Id.

[26] Id.

[27] See generally Bill Pennington & Steve Eder, In Domestic Violence Cases, N.F.L. Has A History of Lenience, N.Y. Times (Sept. 19, 2014), http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/20/sports/football/in-domestic-violence-cases-nfl-has-a-history-of-lenience.html.

[28] NFL Personal Conduct Policy, ESPN (Mar. 13, 2007), http://www.espn.com/nfl/news/story?id=2798214.

[29] Id.

[30] Id.

[31] Id.

[32] Id.

[33] Id.

[34] CB Jones Suspended for 2007 Season, WR Henry Banned Eight Games, Yahoo! Sports (Apr. 10, 2007), http://sports.yahoo.com/nfl/news?slug=playerconduct.

[35] NFL Personal Conduct Policy, supra note 28.

[36] Id.

[37] Marc Sessler, Pacman Jones Ordered to Pay $11.7M in Vegas Shooting, NFL.com (Aug. 3, 2012), http://www.nfl.com/news/story/09000d5d829dfae6/article/pacman-jones-ordered-to-pay-117m-in-vegas-shooting.

[38] Mark Curnutte, NFL Suspends Bengals’ Henry for Eight Games, USA Today (Apr. 11, 2007), http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/sports/football/nfl/bengals/2007-04-10-henry-suspension_N.htm; CB Jones Suspended for 2007 Season, WR Henry Banned Eight Games, Yahoo!Sports (Apr. 10, 2007), http://sports.yahoo.com/nfl/news?slug=playerconduct.

[39] Barry Wilner, Roethlisberger Suspended 6 Games, San Diego Union Tribune (Apr. 21, 2010), http://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/news/2010/apr/21/roethlisberger-banned-6-games/.

[40] Id.

[41] Id.

[42] Id.

[43] Michelle R. Smith, Ex-NFL Star Hernandez Convicted of Murder, Sentenced to Life, Fox 11 News (Apr. 15, 2015), http://fox11online.com/sports/packers-and-nfl/ex-nfl-player-aaron-hernandez-convicted-of-1st-degree-murder.

[44] Ben Volin, Patriots Quickly Ran Out of Patience with Aaron Hernandez, Boston Globe (Jun. 27, 2013), https://www.bostonglobe.com/sports/2013/06/26/patriots-patience-runs-out-quickly-aaron-hernandez/qNdBUXPPz1Qs4Lghtsv4tN/story.html.

[45] Patriots Release Aaron Hernandez, ESPN (June 27, 2013), http://www.espn.com/boston/nfl/story/_/id/9424845/aaron-hernandez-released-new-england-patriots.

[46] Convicted Murderer Aaron Hernandez Sentenced to Life in Prison Without Parole, FoxNews (Apr. 15, 2015), http://www.foxnews.com/us/2015/04/15/verdict-reached-in-aaron-hernandez-murder-trial.html.

[47] Mel Robbins, NFL’s Personal Conduct Policy Fail, CNN.com (Dec. 13, 2014), http://www.cnn.com/2014/12/11/opinion/robbins-nfl-domestic-violence-rules/index.html.

[48] Id.

[49] Id.

[50] Pat McManamon, Johnny Manziel Waived by Browns, ESPN (Mar. 9, 2016), http://espn.go.com/espn/print?id=14933932.

[51] Robbins, supra note 47.

[52] See generally Michael O’Keefe, NFLPA Rips League over Personal Conduct Policy Changes, NY Daily News (Dec. 9, 2014), http://www.nydailynews.com/sports/football/nflpa-rips-league-personal-conduct-policy-article-1.2039890; Ken Belson, NFL Sets Strict Rules for Actions off Field, NY Times (Dec. 10, 2014), http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/11/sports/football/roger-goodell-wont-assess-penalties-under-revised-conduct-policy.html?_r=0.

[53] Belson, supra note 52.

[54] Id.

[55] Id.

[56] Id.

[57] Id.

[58] Owners OK New Conduct Policy, ESPN (Dec. 10, 2014), http://espn.go.com/espn/print?id=12009596.

[59] Id.

[60] Id.

[61] Id.

[62] Id.

[63] Id.

[64] Id.

[65] Mike Freeman, The Ultimate Plan for the NFL to Regain the High-Ground, Bleacher Report (Apr. 1, 2016), http://bleacherreport.com/articles/2628921-the-ultimate-plan-for-the-nfl-to-regain-the-high-ground.

[66] Cindy Boren, Drew Brees Doesn’t Trust Any NFL Investigation Led by Roger Goodell, Washington Post (Apr. 26, 2016), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/early-lead/wp/2016/04/26/drew-brees-doesnt-trust-any-nfl-investigation-led-by-roger-goodell/.

[67] Id.

[68] Arbitrator Upholds NFL’s Use of Paid Leave for Players Under Personal Conduct Policy, ESPN (Apr. 11, 2016), http://espn.go.com/nfl/story/_/id/15179491/arbitrator-upholds-nfl-use-paid-leave-players-personal-conduct-policy.

[69] NFL Approves “Tough” Personal-Conduct Policy, supra note 1.

[70] NFL Personal Conduct Policy, CBS News, http://www.cbsnews.com/htdocs/pdf/NFL_domestic_violence_policy.pdf.

[71] Personal Conduct Policy, NFL (Dec. 2014), http://static.nfl.com/static/content/public/photo/2014/12/10/0ap3000000441637.pdf; NFL’s New Personal Conduct Policy, Workplace Bullying Institute (Dec. 20, 2014), http://www.workplacebullying.org/nfl-13/; NFL Personal Conduct Policy, supra note 28.

[72] NFL Personal Conduct Policy, CBS News, supra note 70.

[73] Id.

[74] NFL Approves “Tough” Personal Conduct Policy, supra note 1.

[75] NFL Personal Conduct Policy, CBS News, supra note 70.

[76] NFL Approves “Tough” Personal Conduct Policy, supra note 1.

[77] Personal Conduct Policy, supra note 71.

[78] Id.

[79] Id.

[80] Id.

[81] Id.; see also The New NFL Personal Conduct Policy, NFL, http://www.cbsnews.com/htdocs/pdf/NFL_domestic_violence_policy.pdf (last visited Oct. 29, 2016).

[82] Kavitha A. Davidson, NFL Finds New Way to Botch an Abuse Case, Bloomberg (Apr. 2, 2015), http://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2015-04-02/nfl-finds-new-way-to-botch-an-abuse-case.

[83] Eric Adelson, NFL’s Due Diligence on Greg Hardy Shows what the Cowboys Lacked, Yahoo!Sports (Apr. 22, 2015), http://sports.yahoo.com/news/nfl-s-due-diligence-on-greg-hardy-shows-what-the-cowboys-lacked-231845683.html.

[84] Id.

[85] John Breech, Cowboys DE Greg Hardy Suspended for 10 Games: 3 Things to Know, CBS Sports (Apr. 22, 2015), http://www.cbssports.com/nfl/news/cowboys-de-greg-hardy-suspended-for-10-games-3-things-to-know/.

[86] Alex Reimer, Browns Release Johnny Manziel After 2 Tumultuous Seasons, SBNation (Mar. 11, 2016), http://www.sbnation.com/nfl/2016/3/11/10878988/johnny-manziel-released-cleveland-browns-rehab-arrest.

[87] Pat McManamon, Roger Goodell Could Punish Johnny Manziel Under Personal Conduct Policy, ESPN (Oct. 23, 2015), http://espn.go.com/espn/print?id=13953369.

[88] Id.

[89] Aaron Wilson, Browns Will Part Ways with Manziel, Houston Chronicle (Feb. 2, 2016), http://www.houstonchronicle.com/sports/texans/article/Cleveland-preparing-to-cut-Johnny-Manziel-6801915.php.

[90] Jill Martin, Johnny Manziel Indicted in Alleged Assault of Ex-Girlfriend, CNN (Apr. 27, 2016), http://www.cnn.com/2016/04/26/us/johnny-manziel-indicted/.

[91] Lindsay H. Jones, Johnny Manziel Suspended Four Games for Substance Abuse, USA Today (June 30, 2016), http://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/nfl/2016/06/30/johnny-manziel-suspended-4-games-substance-abuse/86555946/.

[92] Jeff Hunter, LeSean McCoy Won’t Face Charges from February Bar Fight, Per Reports, SB Nation (Apr. 4, 2016), http://www.buffalorumblings.com/buffalo-bills-news/2016/4/4/11361800/lesean-mccoy-no-charges-filed-bar-fight-philadelphia-da-office/in/10713095.

[93] Id.

[94] Kevin Dillon, LeSean McCoy, Buffalo Bills RB, Will Not be Suspended for Role in Nightclub Brawl (report), Mass Live (Jul. 13, 2016), http://blog.masslive.com/patriots/2016/07/lesean_mccoy_buffalo_bills_rb.html.

[95] Michael Schottey, NFL New Personal Conduct Policy Seems to be Just More of the Old, Bleacher Report (Dec. 10, 2014), http://bleacherreport.com/articles/2295783-nfl-new-personal-conduct-policy-seems-to-be-just-more-of-the-old.

[96] Id.

[97] Id.

[98] Id.

[99] Robbins, supra note 47.

[100] Id.

[101] Id.

[102] Id.

[103] Jack Meyer, Unnecessary Toughness: Throwing the Flag on the NFL’s New Personal Conduct Policy, Ill. Bus. J (Dec. 2, 2015), https://publish.illinois.edu/illinoisblj/2015/12/02/unnecessary-toughness-throwing-the-flag-on-the-nfls-new-personal-conduct-policy/.

[104] Id.

[105] Id.

[106] Player Arrests Down in the NFL as Rice Still Lives ‘Nightmare’, supra note 3.

[107] Id.

[108] Id.

[109] NFL Personal Conduct Policy, CBS News, supra note 70.

[110] Michael Schottey, supra note 95.

[111] NFL Personal Conduct Policy, CBS News, supra note 70.

[112] William C. Roden, With Deflategate Ruling, Roger Goodell is Firmly in Control, NY Times (Apr. 25, 2016), http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/26/sports/football/roger-goodell-nfl-tom-brady-deflategate-appeal.html?smid=nytcore-ipad-share&smprod=nytcore-ipad&_r=0.

[113] Id.

[114] Matt Rocheleau, Few Legal Options Left for Tom Brady to Keep Fighting ‘Deflategate’ Suspension, Boston Globe (Apr. 25, 2016), https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2016/04/25/few-legal-options-left-for-brady-keep-fighting-deflategate-suspension/XeBOApexgGPYqp3S0uuk6J/story.html.

[115] Martin J. Greenberg & Lori Shaw, Deflategate, Sport$Biz Blog (Oct. 1, 2016), https://greenberglawoffice.com/deflategate/.

[116] Don Melvin, Tom Brady’s ‘Deflategate’ Appeal Hearing Ends After 10 Hours, CNN (June 23, 2015), http://www.cnn.com/2015/06/23/us/deflategate-brady-hearing/.

[117] Roden, supra note 112.

[118] Id.

[119] Greenberg & Shaw, supra note 115.

[120] Lorenzo Reyes, Federal Court Reinstated the NFL’s Four-Game Suspension of Tom Brady, USA Today (Apr. 25, 2016), http://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/nfl/2016/04/25/tom-brady-nfl-suspension-reinstated-federal-court-deflategate/83497072/.

[121] Michael McCann, Tom Brady’s Last Shot: Taking Deflategate to the Supreme Court, Sports Illustrated (Jul. 23, 2016), http://www.si.com/nfl/2016/07/13/tom-brady-suspended-deflategate-appeal-supreme-court.

[122] Id.

[123] Id.

[124] Chris Wesseling, NFL to Interview Players Named in AL Jazeera Report, NFL.com (June 27, 2016), http://www.nfl.com/news/story/0ap3000000671338/article/nfl-to-interview-players-named-in-al-jazeera-report

[125] Id.

[126] Michael McCann, Understanding the NFL’s Motive to Suspend Players Implicated by Al Jazeera Report, Sports Illustrated (Aug. 16, 2016), http://www.si.com/nfl/2016/08/15/nfl-al-jazeera-america-peyton-manning-clay-matthews-julius-peppers-james-harrison.

[127] Tom Pelissero, NFL Gives Players Accused in Al Jazeera Story Three Choices — None of Them Good, USA Today (Aug. 16, 2016), http://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/nfl/2016/08/16/julius-peppers-clay-matthews-james-harrison-investigation-nflpa-options/88821918/.

[128] Id.

[129] Id.

[130] Darin Gantt, Clay Matthews: Forced Testimony “Sets a Dangerous Precedent” for Players, NBC Sports (Sept. 2, 2016), http://profootballtalk.nbcsports.com/2016/09/02/clay-matthews-forced-testimony-sets-a-dangerous-precedent-for-players/.

[131] Ken Belson, Roger Goodell’s Power Play, NY Times (Sept. 8, 2016), http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/09/sports/football/roger-goodell-nfl-players-union.html?_r=1.

[132] Id.

[133] Id.

[134] Id.

[135] Id.

[136] Meyer, supra note 103.